CHASE

CHASE

The decline of the 19th-century German school of violin playing - Clive Brown

There has been much recent debate about the notion of 'Schools' of musical performance. It is clear, however, that musicians frequently believed

themselves to belong to a school and often saw themselves in opposition

to another school, which espoused different aesthetic values or technical means. In the history of violin playing, schools

have often been identified by contemporaneous commentators, sometimes when they

perceived the emergence of distinctive technical and stylistic features that

distinguished the playing of one group of violinists from others. This was certainly the case with the school

variously identified as ‘Viotti’, ‘Paris’, or ‘French’ around the beginning of

the nineteenth century. Thus a reviewer of a concert at the Leipzig Gewandhaus

in 1803 noted that ‘It is well known that Messers Rode, Kreutzer, Baillot etc.

form a high-school of violin playing in Paris such as could scarcely be said to

have existed before’ (Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung,5(1802-3), col. 585). And by 1825 G. C.

F. Lobedanz, discussing whether there could be schools in music as there were

perceived to be in painting, stated that a precondition for the existence of

such a school was that its founder must have ‘developed a previously unknown

style, which was acknowledged by the best authorities of his time as a model’ (in article:

‘Gibt es in der Musik, wie in der Malerey, verschiedenen Schulen, und wie wären

solche wohl zu bestimmen?’ Cäcilia, 2(1825), p. 265). With respect

to violin playing, he observed there was a ‘French School, founded by Viotti,

Rode and Kreutzer’, which had been ‘more or less adopted by almost all

present-day violin virtuosos’ (Ibid., p. 267).

The case was somewhat different with the schools that were identified by contemporaries in the middle years of the nineteenth century as ‘Franco-Belgian’ and ‘German’. Whereas the ‘Viotti/Paris/French school’ was seen to have dominated the world of string playing for several decades at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Franco-Belgian school, generally regarded as having its roots in the playing and teaching of Charles de Bériot (1802-70), was perceived to exist alongside and, to some extent, in opposition to a less clearly defined German school (it should be understood that throughout this article the word ‘school’ is used as an historical term rather than a substantial concept). Like the Franco-Belgian school, this German one had also been inspired by the tenets of the Viotti/Paris/French school as interpreted by such influential teachers as Louis Spohr (1784-1859) and Joseph Boehm (1795-1876). Of course, neither school was monolithic, nor did they remain static in their teachings or stylistic precepts. The practices and principles of the Franco-Belgian tradition were moulded and amplified by such influential figures as Henri Vieuxtemps (1820-81), Henryk Wieniawski (1835-80), and Eugene Ysaÿe (1858-1931), while those of the German tradition were further transmitted and developed by pupils of Spohr and Boehm, most notably Ferdinand David (1810-73), Jacob Dont (1815-88), Joseph Hellmesberger (1828-93), and Joseph Joachim (1831-1907). Joachim (a pupil both of Boehm and David), a towering figure in late nineteenth-century performance and a revered teacher, was widely seen by the end of the century as the personification of a distinctive tradition in German violin playing. By the early years of the twentieth century, however, the artistic and technical precepts that lay at the core of this German tradition were becoming increasingly out of touch with the changing tastes of the day. Within a generation of Joachim’s death in 1907 few of the aesthetic aims, and virtually no trace of the distinctive techniques that had characterised his approach to violin playing (laid out in painstaking detail in the Joachim and Moser Violinschule of 1905) survived in the world of professional music making.

The third volume of the Violinschule begins with a series of ten short essays entitled ‘On Style and Artistic Performance’ (Vom Vortrag). Although these was written by Moser, they undoubtedly reflected Joachim’s views, for in his preface to the first volume, Joachim stated that ‘even the most insignificant questions of detail were subject to joint scrutiny and nothing was decided until we were in total agreement.’ (Joseph Joachim and Andreas Moser, Violinschule 3 vols. (Berlin,1905) I, p. 4. My translations; Alfred Moffat’s English translation is not always reliable.) Moser’s final essay discusses changes in violin playing that had occurred during Joachim’s lifetime. It begins with a reference to Wagner’s account of the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra’s performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in 1839, in which he praised the ‘masterly skill’ of the French string players. Moser commented that ‘the violinists of the celebrated Conservatoire Orchestra were at that time still fully in possession of the classical traditions of the Italian bel canto, and of a bowing technique that is closely related to it,’ adding that, as pupils of Viotti, Rode and Kreutzer, or at least of Baillot and Habeneck, they ‘came under the influence of a school of which almost all trace has since disappeared in France’ (Ibid, III, p. 32). In other words, Moser believed that the newer Franco-Belgian School had almost entirely displaced the older Viotti/Paris/French School.

Moser characterised the older school as teaching ‘above all a singing tone on the violin, free from mannerism and artificiality’, a left-hand technique required by the nature of the instrument, and a ‘supple and independent style of bowing that served the characteristics of the various types of bowstroke’. He stressed that this was not merely a style and technique appropriate to virtuoso violin playing but that the ‘teaching and technical acquirements of that school lay at the roots of the treatment of the instrument by all masters of instrumental music from Haydn to Mendelssohn.’ Having identified Joseph Boehm (a pupil of Rode), alongside Dittersdorf, as one of the agents by which this Italian style of playing reached Vienna, he referred to Spohr’s residence in the city, describing him misleadingly as a product of the Mannheim School, which ‘always cherished a special predilection for the classical Italian-French style of violin playing, to which their own school was closely related.’ He completed his panegyric on the style of playing he believed to have been cultivated by members of this Italian-French-German school with the statement:

If we go on to consider that Joseph Haydn wrote the majority of his string quartets and all his violin concertos for his friend and intimate, the Italian artist L[uigi] Tomasini, that Mozart was brought up as a violinist by his father in the Tartini tradition, and Beethoven was alternately connected with Kreutzer, Rode and Böhm [sic], it is clear that we must look upon the compositions and studies of that classical school as the violinistic model and standard for all the chamber and orchestral music that was created on Austrian soil; and only those who make the teaching of that school their own will be able to satisfy the demands this music makes on the performer’s technical capabilities, so that the animating spirit of these art-works can receive meaningful expression.

Moser concluded his introductory remarks with the observation that the essence of this tradition could be summed up with Tartini’s dictum: ‘Per ben suonare, bisogna ben cantare’ ('to play well it is necessary to sing well') (Ibid, III, p. 32).

With these arguments and assertions Moser advanced the case for seeing a direct and intimate connection between Joachim’s approach to violin playing and the principles that had determined the treatment of the instrument by great composers from Haydn to Mendelssohn (and, by implication, Brahms). Moser’s portrayal of the characteristics and ideals of this school and his assertion that Joachim, as its heir, was in a position to perpetuate its teachings may be problematic from the point of view of historical accuracy, yet there can be no doubt that Joachim, a protégé of Mendelssohn in the early 1840s, genuinely believed himself to be a guardian of the true traditions of classical violin playing as he understood them.

Underlying Moser’s argument, but in fact central to it, is the supposition that the principles and practices preserved and disseminated by Joachim through his teaching and playing offered the only key to performing the German musical classics in the manner intended by their composers. The purpose of his exposition becomes clear when Moser turns to a consideration of the direction string playing began to take in the second half of the nineteenth century; he immediately refers to ‘Franco-Belgian violinists’ and the ‘peculiar aspect’ works by Bach, Mozart and Beethoven take on in their hands. The reason for this, he writes, is that although these virtuosos may possess an astonishing left-hand technique, they have ‘not only completely forgotten that healthy and natural method of singing and phrasing, that is based on the bel canto of the old Italians [...] but have continuously offended against it.’ After further criticism of their bowing and tone production ‘which aim merely at sensuousness of sound’ and fail to achieve the ‘characteristic qualities of different bowstrokes’, he condemns them outright because ‘they do not bring out the spirit of the art-work they imagine they are playing, but merely exhibit faults and mannerisms that result from deficient bowing, hand in hand with those bad habits of singing, which fail to take account of the most elementary demands of natural melody.’ Although he admitted that among the products of this tendency there might be some ‘truly sympathetic and even distinguished artists’, this seems more like unwillingness to offend individuals than a genuine acknowledgement of the validity of alternative approaches (Ibid, III, p. 32f).

Moser’s account of how this situation came about clearly reflects Joachim’s view of the developments in violin playing he had experienced during his career. Joachim was born at the time of Paganini’s epoch-making tours of Europe north of the Alps, which shattered any notion of the hegemony of a ‘Viotti/Paris/French School’, and he must quickly have become aware during his early youth of the tensions this phenomenon created. As a student of Boehm in Vienna, around 1840, he was in the midst of a musical society that was still trying to come to terms with the technical and aesthetic implications of Paganini’s playing. Under Boehm’s tutelage he will have been made ‘acquainted with all the new publications of violin literature, for he [Boehm] was of the opinion that only all-round technical ability made for independent violin playing.’ (Andreas Moser, Joseph Joachim. Ein Lebensbild, 2nd edn, 2 vols. (Berlin, 1908–10), I, p. 30. My translation.) Joachim’s study material at this time may already have included music by Paganini, but it is certain that he played Paganini in Leipzig shortly afterwards under the tuition of Ferdinand David (who was to publish an annotated edition of Paganini’s Caprices in the early 1850s), for he wrote to Boehm on 15 October 1844, telling him that he was working at music by Spohr, Paganini and Bach.(Letters From and To Joseph Joachim,selected and trans. Nora Bickley (London, 1914), p. 2) It is nevertheless clear that at the root of Joachim’s schooling under Boehm were the fundamental precepts of the Viotti/Paris/French style as it was practised, in Lobedanz’s words, ‘by almost all present-day violin virtuosos’ during the period immediately preceding Paganini’s advent in Vienna. Thus Moser focused on the aspects of Paganini’s influence that Joachim believed to have been most damaging. Attempting to emulate the ‘tremendous technical feats on the fingerboard’, which were peculiar to Paganini’s idiosyncratic technical abilities, ‘caused his imitators not only an immense expenditure of time and labour, but also meant the denial of the nature of our instrument’. The neglect of the instrument’s singing qualities soon led to the ‘utter downfall of bow technique in its classical sense’. French violinists employed ‘artificial bowstrokes’ to achieve astonishing effects, but their ‘stiff bowing’ inhibited their ability to achieve ‘vocal and spiritual ends.’ This meant that they could not interpret musical art-works ‘in the spirit of their creator’. At that point Moser had the difficulty of explaining the career of another Boehm pupil, Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (1812?-1814), whom Joachim deeply admired. Ernst had been one of the most successful of Paganini’s imitators, but Moser explained that he escaped the worst consequences of developing his virtuoso technique because of ‘his healthy musical nature and the training he had received under Joseph Böhm,’ and because he already had ‘such an established artistic personality when he went to Paris that he was quite safe from the dangers to which, to the detriment of art, his French rivals succumbed’ (Joachim/Moser, Violinschule, III, p. 33).

Having dealt with this difficult issue, Moser returned to his description of the ‘spiritual decay’ of Franco-Belgian violin playing, which required him to discuss the career of Henri Vieuxtemps, the most prominent ‘Franco-Belgian’ violinist of his time. Elsewhere Joachim had expressed the view, that although he ‘greatly admired Vieuxtemps as a solo player’, he considered him less impressive in chamber music ‘because – like most violinists of the Franco-Belgian school in recent times – he adhered too strictly to the lifeless printed notes when playing the classics, not understanding how to read between the lines.’ (Moser, Joseph Joachim, II, p. 292) It was impossible for Moser (Joachim) to deny that Vieuxtemps was ‘just as much a brilliant virtuoso as an extraordinarily gifted composer for his instrument’, but he was characterised, with undisguised disapproval, as ‘the most typical representative of that kind of musical pathos that is commonly designated “modern French”.’ Moser grudgingly conceded that although he did not ‘question the right of this kind of pathos to exist as such’, its influence beyond its own sphere, particularly through the agency of Vieuxtemps’ imitators had been disastrous (Joachim/Moser, Violinschule, III, p. 33). These inadequate violinists,

in order not to seem uninteresting when inner feeling failed or, when, where it was present, it could not express itself because of bad mannerisms, made up for the lack of natural expression in cantabile by means of that flickering tone production resulting from unbearable vibrato, which combined with a portamento that was mostly incorrectly executed, is the deadly enemy of all healthy music-making.

As a result of these deficiencies, Moser explained:

the epigones of those masters who a century ago approached so closely to the ideal that is noblest in musical performance, now not only debase the compositions of the classical German masters by treating them in an operatic manner, but are no longer capable of interpreting even the old masterpieces of their own country with purity of style. France today probably does not possess a violin player who is capable of rendering Viotti’s 22nd concerto in a manner worthy of that wonderful work or its creator (Ibid, III, p. 34).

In a final condemnation of those violinists, Moser protested:

greater distinctions between the classical exponents of French violin playing and representatives of the newer Franco-Belgian tendency can hardly be imagined: on the one side natural singing and healthy music-making, on the other bad performance mannerisms and a total lack of style! That which strikes us as so alien in the performance of classical works by the more recent Franco-Belgian virtuosos is only to the smallest extent to be put down to differences in national sensitivities, for at an earlier period when the musical world was still under the influence of a universal language, rooted in Italian singing, those distinctions were hardly perceptible (Ibid, III, p. 35).

Although these words were penned by Moser, there can be little doubt that they precisely reflected Joachim’s opinion. Indeed, scrutiny of Moser’s later writings, published years after Joachim’s death, when the style he had championed had been virtually ousted from the public sphere, reveals almost nothing of this disapproval of the Franco-Belgian School’s style, and its exponents’ inability to perform the music of the classical masters in an appropriate manner. Moser’s Geschichte des Violinspiels (1923) levelled no criticism directly at players such as Kreisler for his vibrato, or Thibaut for his portamento, which were of a kind that must have made Joachim turn in his grave, even though the German classics lay at the heart of the repertoire of both these violinists. (Andreas Moser Geschichte des Violinspiels (Berlin, 1923), p. 462 (Thibaut) and p. 472f (Kreisler). He avoids discussion of schools of playing in his own time. In the Geschichte des Violinspiels Moser failed to discuss portamento, as such, at all and levelled only one barbed shaft at vibrato usage, in the final pages of the book, where he referred to ‘the abuse of this fashionable violinistic disease of our time,’ about which ‘even whole books that preach its continual use have recently been published’ (Ibid, p. 564).

*

At the distance of a century it is difficult for us to appreciate the distinctions between stylistic practices that were so apparent to people in the early twentieth century and provoked such strong feelings. Differences of technique and style between the ‘conservative’ and ‘progressive’ string players of the period are subtle and complex, and the relative importance of particular aspects of performing practice did not all change at the same rate or in the same manner. Early recordings, however, can complement or elucidate written texts, allowing us greater insight into the changing aesthetics and practices of the period than either type of evidence provides on its own. But by the time recording becomes available, the style of violin playing advocated by Joachim was almost dead. Although Joachim himself made five short recordings in 1903, few players who were regarded at the time as faithful representatives of his style were considered worthy of the recording studio during the next couple of decades.

Among Joachim’s later pupils who made recordings were Karl Klingler (b. 1879), and his great-niece Adila Fachiri (b. 1886); but both of these players were trained at a time when Joachim’s style of violin playing was already coming to be seen by most younger players as old-fashioned, and their recordings reveal a curious mixture of older and newer traits. Karl Klingler pursued a successful career in Berlin until the 1930s as leader of a quartet that was widely regarded as the successor to Joachim’s quartet, but he did not establish a reputation as a solo player. Moser remarked that ‘despite the excellent state of his technical capability he has not really been able to make his mark on the wider public’ (Moser Geschichte, p. 553). Klingler’s recordings, apart from a movement of a Mozart Duo, are all of quartets. The recordings date from 1911-1934. The earlier ones contain many features that suggest kinship with Joachim’s chamber music performances, in some of which Klingler had taken part during his master’s last years, but notwithstanding Carl Flesch’s comment in 1933 that Klingler ‘has not yet succeeded in getting away from the spiritual fetters of his teacher, which have held him in bond for thirty years’ (Carl Flesch The Memoirs of Carl Flesch, trans. H. Keller (London, 1957), p. 82), the recordings suggest a progressive, if cautious assimilation of more modern vibrato practice, alongside characteristics such as portamento, bowing and treatment of rubato that remained closer to Joachim’s style. In Adila Fachiri’s recording of Beethoven’s Violin Sonata op. 96, made with Donald Francis Tovey in 1928, her occasional portamento is light and her vibrato quite obvious and frequent in cantilena passages, though not entirely continuous, producing a sound noticeably different from Joachim’s. Her playing also exhibits little of Joachim’s approach to rhythmic flexibility, especially agogic accent. Tovey is closer to Joachim in this respect. (As a young man Tovey had frequently accompanied Joachim. See Mary Grierson, Donald Francis Tovey. A Biography Based on Letters, (London, New York, Toronto, Oxford University Press, 1952))

Leopold Auer (b. 1845), who studied for two years with Joachim in 1861-3 is the oldest of his students to have made any recordings, but he was even older than Joachim when he did so in 1921 and it is difficult to know to what extent age may have affected his playing (Leopold Auer, Violin Playing as I teach it (London, 1921), p. 4). In any case, as an influential teacher in St Petersburg for many years, he had undoubtedly developed his own approach to violin playing that will have differed from Joachim’s in significant respects, not least because of his development of the so-called ‘Russian’ bow grip. (See Carl Flesch, The Art of Violin Playing, trans F. Martens (New York, 1924, revised edition 1933), p. 54, and Leopold Auer, Graded Course of Violin Lessons (New York, 1925), I, p. 12.) About the time Auer made his recordings he railed against excessive use of vibrato and portamento in terms even more violent than Joachim’s (Auer, Violin Playing, p. 59ff). Although his recordings reveal rather more frequent use of vibrato than one might expect, it is far closer to Joachim’s, both in terms of application and execution, than to that of any of his own students (among them Heifetz, Elman, and Zimbalist) who made gramophone recordings. In his recording of Tchaikowsky’s ‘Mélodie’ Auer employed prominent portamento, including the type of ‘French’ portamento, much more frequently than his treatment of the subject in Violin Playing as I teach it would suggest, and in ways that appear to contradict his own instructions (Ibid., p. 63f).

The only one of Joachim’s older recorded pupils, who was clearly and frequently described by contemporaries as playing in a style that closely resembled his was Marie Soldat (1863-1955). (After her marriage in 1889 she was variously known as Roeger-Soldat and Soldat-Roeger (or Röger). Some sources, including Grove 3, give her birth year as 1864.) In 1883 Clara Schumann, greatly impressed by Soldat’s playing of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, noted in her diary ‘I think she has a future. One immediately hears that she is of the Joachim School’ (quoted from Barbara Kühnen Marie Soldat. Aspekte der Biographie einer vergessenen Musikerin. Wissenschaftliche Hausarbeit zur Ersten Staatsprüfung für das Lehramt an Gymnasien. Universität Kassel: Unveröffentlichtes Typoskript, 1995, p. 29 on the MUGi website http://mugi.hfmt-hamburg.de/A_lexartikel/lexartikel.php?id=sold1863, accessed 3/5/2013).

During Soldat’s first visit to England in 1888 The Musical Times commented on her performance of the Brahms Violin Concerto: ‘Her method and style are those of her master, who must have found it an easy task to direct the studies of a young lady so highly gifted with musical feeling and intelligence’ (The Musical Times, 29(1888), p. 218). And in 1896 a reviewer of her quartet’s performance of works by Mozart, Beethoven and Mendelssohn in Berlin observed: ‘It appears to me as if the dashing leader has best understood Joachim’s style. With closed eyes one could believe that the Master were sitting at the first desk.’ (Kleines Journal, 19 Jan. 1896, quoted in Urtheile der Presse über das Streichquartett Soldat-Roeger (Vienna, 1898), p. 2f.) Although Moser, in his Geschichte des Violinspiels, might have cited Marie Soldat alongside Klingler as a worthy standard bearer of their master’s ideals, he confined himself to characterising her in a short paragraph as having ‘made a resounding name just as much through the performance of classical compositions, including the Brahms Violin Concerto at the time of her tours with the Meiningen Orchestra under Steinbach, as through her leadership of a string quartet consisting exclusively of ladies, which she founded in Vienna’ (Moser, Geschichte, p 549). As Moser’s account suggests, however, she enjoyed a high reputation in her youth both as soloist and quartet player. She was particularly noted for her performances of Brahms; in the year after Joachim’s death The Musical Standard remarkedthat ‘in Brahms’ Violin Sonatas Frau Marie Soldat-Roeger has no rival’ (The Musical Standard, 30(1908), p. 302). By the time she made her only recordings, in 1926, she was in her sixties, and we cannot know to what extent her playing might have changed in the intervening years. It seems almost inconceivable that she could have been completely impervious to the developments in violin playing that were happening around her, yet her style in those recordings still displays remarkable similarities to the tantalising glimpses of Joachim’s that can be heard in his 1903 recordings.

Marie Soldat’s position in the history of nineteenth- and twentieth-century violin playing has received little attention. Biographical material from the diaries of Margaret Denecke and other English sources are examined in Michael Musgrave, ‘Marie Soldat 1863 –1955: An English Perspective’, in Reinmar Emans and Mattias Wendt (eds), Beiträge zur Geschichte des Konzerts Festschrift Siegfried Kross zum 60. Geburtstag, (Bonn, Gund Schröder, 1990), p. 326. Further biographical and bibliographical information can be found on the Music and Gender website (http://mugi.hfmthamburg.de/A_lexartikel/lexartikel.php?id=sold1863) and in publications by Barbara Kuhnen: 'Marie Soldat-Roeger (1863–1955)', in Die Geige war ihr Leben. Drei Frauen im Portrait, ed. Kay Dreyfus and others, (Strasshof, 2000, pp. 13–98) and '"Ist die Soldat nicht ein ganzer Kerl?‘ Die Geigerin Marie Soldat-Roeger (1863–1955)', in: 'Ich fahre in mein liebes Wien'. Clara Schumann: Fakten, Bilder, Projektionen, hed. Elena Ostleitner & Ursula Simek (Wien, 1996), pp. 137–150; see also her unpublished dissertation: Marie Soldat. Aspekte der Biographie einer vergessenen Musikerin. (University of Kassel, 1995). The most substantial recent discussion of her violin playing is in David Milsom’s online essay, ‘Marie Soldat-Roeger (1863-1955): Her Significance to the Study of Nineteenth-Century Performing Practices’ (http://www.leeds.ac.uk/music/dm-ahrc/docs/Marie-Soldat-Roeger-Article/MarieSoldat-RoegerandherSignificancetotheStudyofNineteenth-CenturyPerformingPractices.doc), which reflects research we undertook together during his AHRC Fellowship at Leeds University between 2006-9. Despite her neglect in the literature, the importance of her recordings for understanding the momentous changes in technique and aesthetics that took place in the early twentieth century cannot be overestimated. These recordings, which reveal a very impressive technique despite her age, preserve a style of playing that must already have seemed distinctly old-fashioned to younger musicians. Her apparent unwillingness to adapt significantly to the prevailing taste of the time, rather than any failure of her technical powers, was almost certainly a key factor in the decline and virtual eclipse of her public career. Not only her fidelity to Joachim’s portamento and vibrato aesthetic, but also her style of bowing and phrasing, as well as her rubato were increasingly out of step with public taste. The brief entry on her by Walter Cobbett in the 1927 edition of Grove’s Dictionary is written as though her career was over and concludes with the unenthusiastic comment that she ‘had a following among those who admire solid before brilliant acquirements.’(Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 3rd edn, IV, p. 800) Paul David’s judgment, that Joachim’s similar style of playing ‘appeared especially adapted to render compositions of the purest and most elevated style’ (Ibid, II, p. 779, reprinted with additions from the 1904 2nd edition of Grove) suggests the extent to which taste had changed since the early years of the century. In fact, however, as late as the seasons of 1929 the critic of a London journal reviewed sonata performances by Marie Soldat and Fanny Davies appreciatively (Gamba, The Strad, 40(June 1929), pp. 69-70); it was a lasting impression, for in the following season he recalled: 'I heard them play a Brahms sonata last year and it was memorable' (Gamba, The Strad, 41( June 1930), pp. 70-71).

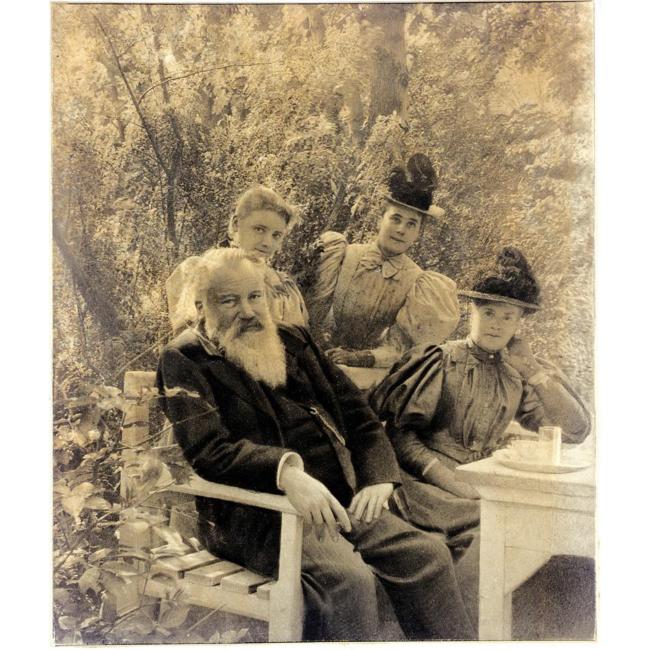

The biographical details of Soldat’s early career may be briefly summarised. Born in Graz she first studied violin with a local musician, Eduard Pleiner, between 1871 and 1877, then with August Pott, who had been a pupil of Spohr in the early 1820s. In summer 1879, during a concert tour of Austrian spas, her playing so impressed Brahms that he introduced her to Joachim, and in the autumn of the same year she enrolled at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin, where she studied violin with Joachim and piano with Ernst Rudorff, winning first prize in the Mendelssohn competition in 1882 for a performance of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto. After her graduation she remained in Berlin until 1889 and continued to receive lessons, free of charge, from Joachim. During this time she made her debut with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in December 1882 with Bruch’s Kol Nidrei. In the spring of 1884 in Vienna she gave a series of performances, including Spohr’s Eighth Violin Concerto, which was considered ‘a real delight’ and ‘after which there was no end of hearty applause’ (The Monthly Musical Record, ‘Music in Vienna. [From our special correspondent]’,14(1884), p. 104), as well as Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, which ‘obtained for her a genuine triumph,’ and Brahms’s G major Violin Sonata (The Musical World, ‘Foreign Budget. (From Correspondents)’, 62(1884), p. 229). Then, in 1885, she became the first female violinist to play Brahms’s Violin Concerto in public, giving a stunning performance in Vienna, conducted by Hans Richter, after which ‘she was called for with a storm of applause again and again.’(The Monthly Musical Record, ‘Music in Vienna. [From our special correspondent]’, 15(1885), p. 81) The delighted composer is reported to have exclaimed: ‘Isn’t little Soldat a brave fellow? Isn’t she equal to ten men? Who could do it better?’ (‘Ist die kleine Soldat nicht ein ganzer Kerl? Nimmt sie es nicht mit zehn Männern auf? Wer will es besser machen?’ (Max Kalbeck, Johannes Brahms (Berlin, 1904-1915), V, p. 159) And he presented her with his own richly bound full score. Three years later she gave a highly successful performance of the concerto in London (it was reviewed enthusiastically in The Musical World, The Musical Times, and The Saturday Review among others), which marked the beginning of an association with Britain that lasted until the 1930s. Her close musical relationship with Brahms lasted until the end of his life; they played together and she was said to be his ‘favourite violinist for his sonatas’ (The Musical Times,74(1933), p. 548). In Fig. 1 Soldat is standing immediately behind Brahms

Fig. I: Brahms with Marie Soldat (left) and two other ladies c. 1894

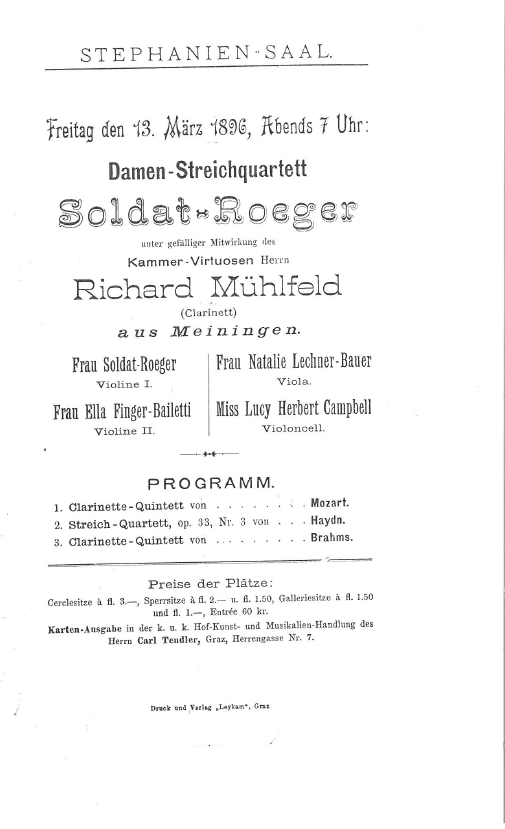

Shortly before the composer’s death, Soldat’s quartet, with Richard Mühlfeld, played him his Clarinet Quintet Op. 115, a work they had already performed together. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Programme of Concert in Graz 13 March 1896 (In private possession)

Among the most significant aspects of her activity in these early years was her involvement in quartet playing. In 1884 it was already reported that she was ‘said to play also in quartets in a superior manner’ (The Monthly Musical Record,14(1884), p. 105). Three years later she established her first professional ladies string quartet in Berlin, but this lasted just one season, for in 1889 she married, gave birth to a son the following year and retired temporarily from professional life. She resumed her musical career in 1892, however and founded a second ladies string quartet in Vienna in 1894 with the same cellist as in Berlin, Lucy Campbell (later replaced by Leontine Gärtner), and two other Viennese musicians, Ella Finger-Bailetti (later Else von Plank) and Natalie Bauer-Lechner, as second violin and viola (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 From left to right Marie Soldat, Lucy Campbell Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Ella Finger-Bailetti

Many early reviews of Soldat’s quartet playing evince great enthusiasm. The contrast between the cool retrospective estimation of her violin playing in 1927 and the positive reaction that had greeted her early performances is striking.

Soldat’s continuing relationship with Joachim is well documented. During her 1888 concert tour to England she and Joachim played together on several occasions, and newspaper reports show that they continued to collaborate closely until at least 1901. Among the material in a private Viennese collection belonging to descendents of Ella Finger-Balletti and Natalie Bauer-Lechner is a fan on the segments of which are inscriptions typical of an autograph album. Across the three central segments is a portrait of Joachim by Ludwig Michalek together with, in Joachim’s hand, a musical quotation of the beginning of Brahms’s A minor String Quartet and a dedication ‘Zum Andenken an das / Berliner Quartet / dem lieben Mitglied / des Wiener Quar / tets / Joseph Joachim / Berlin d. 5 Febuar / 1897’ (Fig. 4).

The similarity of her manner of playing to Joachim’s was apparently both a blessing and a curse for Marie Soldat. It was a significant factor in her rise to prominence, but after the turn of the century it seems increasingly to have become a hindrance to the further development of her career. The growing popularity and influence of the style of the Franco-Belgian violinists, against whom Joachim and Moser had directed their barbs in the 1905 Violinschule, rapidly made the markedly different sound and style espoused by Joachim and other violinists who shared his aesthetic seem outmoded. Joachim himself had such a firmly established reputation that he retained his following until his death in 1907 (despite recognition that his technique was no longer entirely reliable in later years). But by that date the tide of public taste was turning; in the early years of the twentieth century, and especially after the First World War, the rising generation of musicians and music lovers were predominantly concerned with ‘progress’ and there was an increasingly wholesale rejection of ideals and practices associated with the nineteenth century. In this context the later representatives of Joachim’s school found that they had either to adapt their playing or reconcile themselves to a slow but inexorable decline in popularity. While Klingler managed to adapt to a certain extent, Marie Soldat seems to have remained much more faithful to the style of the 1880s. The situation is nicely illustrated by a journal article in 1910, which described her as ‘a very interesting personality amongst the lady violinists of today, not only on account of her qualities as an artist, but also because she is the representative of a class which is rapidly becoming rare. She represents the Joachim school at its best period, and is imbued with all the traditions of the great classical school’ (Barbara Henderson, ‘Marie Soldat-Roeger’, The Strad, 21(1910), p. 362).

Marie Soldat’s recordings, therefore, offer us a remarkable glimpse into the rapidly darkening twilight of a nineteenth-century tradition of violin playing that had flourished for more than a century. They reveal a quite different approach to vibrato, portamento, bowing, phrasing, and rubato than that of the vast majority of recorded violinists.

Vibrato

To modern ears it is the treatment of vibrato that most obviously differentiates string players recorded during the first decades of the twentieth century from one another. This is not only a question of whether they used it selectively or more continuously, but also a matter of how they executed it and where they employed it. For Joachim, as for all nineteenth-century treatise writers, vibrato was only to be used as an occasional ornament. In his view ‘a violinist of taste and healthy sensitivities will always recognise the steady tone as the norm and use vibrato only where the requirements of the expression make it absolutely necessary’ Joachim/Moser, Violinschule, II, p. 96a). Thus the Joachim and Moser Violinschule reiterated the orthodox guidance that had prevailed throughout the nineteenth century in all the methods that addressed the matter (some ignored it altogether), which was to treat vibrato as an embellishment, to use it only in appropriate places, to vary the rapidity of the oscillations, and to ensure that its amplitude remained very narrow. (See Clive Brown, Classical and Romantic, p. 545ff.) In fact, rather than including a wholly original section on the subject, more than half of the one-page treatment of vibrato in the technical part of the 1905 Violinschule (it warranted another page in Moser’s essays in volume 3) was quoted verbatim from Spohr’s Violinschule of 1833 (Joachim/Moser Violinschule, I, p. 96).

Not until 1910 did a treatise appear in which continuous vibrato as an aspect of beautiful tone production was openly advocated. (Siegfried Eberhardt, Der beseelte Violin-Ton (Dresden, 1910), English translation as Violin Vibrato its Mastery and Artistic Uses (New York, 1911)). By that date, however, recordings make it abundantly clear that most prominent string players were already employing vibrato more as a continuous element of tone than as an ornament.On the other hand, recorded violinists born before the last quarter of the nineteenth century, and many born somewhat later, did not use a fully continuous vibrato; they tended to employ it on most or all longer notes, but left many shorter ones without noticeable vibrato. Joachim’s 1903 recordings, therefore, in which it is still an occasional ornament (many notes having no detectable vibrato), stand in sharp contrast to the majority of other early recordings of concert violinists. At the beginning of the twentieth century, however, there were undoubtedly still many violinists, not celebrated enough to have made solo recordings at that time, who employed vibrato even less than Joachim, or not at all; the playing of the un-named violinist who provided an obbligato for the castrato Moreschi in the Bach-Gounod ‘Ave Maria’ in 1904 reveals no trace of vibrato (Opal CD 9823).

In 1933 Carl Flesch, a ‘reformer’ of violin technique, and advocate of more continuous vibrato, who considered that ‘even the greatest violinistic genius will play out of tune without a levelling and corrective vibrato’ (Flesch, Memoirs, p. 21), described the changes he had observed in his own lifetime, stating that ‘even in 1880 the great violinists did not yet make use of a proper vibrato but employed a kind of Bebung, i.e. a finger vibrato in which the pitch was subject to only quite imperceptible oscillations’, and observing that it was ‘regarded as unseemly and inartistic’ to use vibrato ‘on relatively inexpressive notes’. He identified Ysaÿe as ‘the first to make use of a broader vibrato’ and attempting to ‘give life to passing notes’, and Kreisler as not only resorting to ‘a still broader vibrato’, but also trying ‘to ennoble faster passages’ with it (Ibid, p.120). Kreisler himself believed that what he referred to as ‘French’ vibrato went back further than Ysaÿe, identifying Wieniawski as having ‘intensified the vibrato and brought it to heights never before achieved’, and also stating, rather implausibly, that Vieuxtemps (fifteen years older than Wieniawski) ‘also took it up’. Of course Kreisler could not have personally experience the playing of Wieniawski or Vieuxtemps. The supposed founder of the so-called Franco-Belgian School, Charles de Bériot, was, on the evidence of his Méthode de Violon (1858), just as opposed to frequent vibrato as Spohr and Baillot. He asserted that Ysaÿe ‘became its greatest exponent’ (Louis Paul Lochner, Fritz Kreisler (London, 1951), p. 19), and considered himself his direct heir in this respect, although Kreisler’s own vibrato was distinctly more pronounced and continuous than Ysaÿe’s.

Moser, as the quotation from his Geschichte des Violinspiels indicates (footnote 18), remained un-reconciled to the new aesthetic. He was certainly not alone, and resistance to it continued after his death. In 1927 F. Bonavia labelled vibrato as ‘a curse’, calling it ‘death the leveller - for it kills all musical tone’ and at the climax of his vehement attack declared: ‘The fact that vibrato in excelsis is only useful and indeed necessary in the jazz band, where it matches the bleating of the saxophones and the yawning of the trombones, ought to be a sufficient deterrent. Is it not pretty obvious that what suits the slobbery tunes of the jazz-band will not do for music?’(The Musical Times,68(1927), p. 1077) In contrast, Boris Schwarz (1906-83), just old enough to have heard a few late exponents of the older style of vibrato, was typical of younger violinists who had grown up with continuous vibrato. He considered that with its adoption, ‘the violin became a much more sensuous-sounding instrument, and the public loved it. Soon, a violinist with the old-style vibrato had no chance of being successful’ (Boris Schwarz, Great Masters of the Violin (London, 1984), 285-6). Schwarz’s use of the word ‘sensuous’ is significant, for it is precisely the substitution of ‘sensuousness’ (specifically condemned by Moser) for ‘healthy music-making’ (Joachim/Moser, Violinschule, III, 35) that lies at the core of the Joachim and Moser diatribe. That this tension between ‘moral health’ and ‘sensuality’ in violin playing was current at the time is suggested by Flesch’s extraordinary evocation of the effect of Kreisler’s vibrato on young violinists around the turn of the century, as creating ‘an unrestrained orgy of sinfully seductive sounds, depravedly fascinating, whose sole driving force appeared to be a sensuality intensified to the point of frenzy’ (Flesch, Memoirs, p. 118).

Towards the end of his Geschichte des Violinspiels, Moser praised Karl Klingler for his resistance to the vibrato epidemic (Moser, Geschichte, p. 564), approvingly quoting a passage from Klingler’s recently published Grundlage des Violinspiels (1921), which warned against making the vibrations so wide that the pitch is no longer clear, complaining that ‘unfortunately this widespread bad habit, which to the universal detriment of taste is only too often heard, even from famous violinists, particularly in high positions.’ Although Klingler also reiterated the old teaching that vibrato, as a ‘means of expression’, should only be used ‘where it is supported and justified by excitement or feeling’ (Karl Klingler Über die Grundlagen des Violinspiels (Leipzig, 1921), 18f. See also Leopold Auer’s much more vehement strictures against vibrato in his Violin Playing as I teach it). It is clear from the later Klingler Quartet recordings that, as stated above, he developed a vibrato quite different from Joachim’s. Even in the early recordings Klingler seems to leave few longer notes without at least a hint of vibrato, and in the later ones it is more continuous and broader, though still discreet by comparison with most contemporaries.

Marie Soldat’s recordings, on the other hand, reveal a vibrato usage that closely resembles Joachim’s, both in placement and execution. This is perhaps not surprising, since her style was fully formed by the early 1880s; but it sets her apart from her exact Austrian contemporary Arnold Rosé, whose recordings show him to have used a much more continuous and conspicuous vibrato, which may perhaps help to explain the greater longevity of his career. Carl Flesch described Rosé’s vibrato as ‘noble if a little thin’ (Flesch, Memoirs, p. 51); it was certainly much narrower and less continuous than Flesch’s, which to judge from his recordings was modelled on Kreisler’s. In comparison with other violinists during the early years of the twentieth century, therefore, Soldat’s very sparing use of vibrato may have contributed to adverse reactions to her tone. An otherwise admiring reviewer in 1907 remarked that ‘the quality of her tone struck one as being rather thin’ (The Musical Standard, 28(1907), p. 345). This contrasts with a comment a few years earlier about Ysaÿe, with his much more prominent vibrato, creating ‘quite a sensation, the tone being so rich and full’ (The Violin Times, 8(1901), p. 146). But it also contrasts strongly with a review of Soldat’s performances in London in 1888, when Ysaÿe’s style of vibrato will have been unfamiliar in England, which elicited the comment that in a performance of a Spohr duet with Joachim, she demonstrated ‘the same powerful tone and mastery over her instrument as she had done in Brahms’s difficult concerto’ (The Musical Times,29(1888), p. 217).

The vibrato in Soldat’s performance of the Largo from Bach’s Solo Sonata BWV 1005 is remarkably like Joachim’s in the Adagio from BWV 1001; it is detectable only on a few longer notes. The rapid Prelude from Bach’s E major Partita BWV 1006, provides little opportunity for it, but it occurs on two longer notes in the final bars. In the Adagio from Spohr’s Ninth Concerto she sometimes used vibrato where Spohr did not mark it in the annotated version in his Violinschule (for instance the second bar), but there are also places where she ignores his wavy line and plays a pure, un-vibrated note, especially in higher passages on the E-string. Many sustained notes in her performance of the Adagio have no discernible vibrato, and she was consistent in playing the longer notes that occur on weak beats at the end of a phrase without any vibrato at all. In the Beethoven F major Romance she used vibrato somewhat more often than Joachim employed it in his own C major Romance, but it is remarkably similar to his, recalling the finger vibrato described by Flesch as Joachim’s ‘thin-flowing quiver’; and like Joachim she scarcely used it at all on higher notes. Vibrato is used rather more frequently in the arrangement of Schumann’s ‘Abendlied’, a favourite encore piece of Joachim’s, but, as in the other pieces, it is very discreet. The recording in which vibrato is most obviously used is Wilhelmj’s arrangement of Bach’s Air for the G string, corresponding with nineteenth-century evidence that vibrato was more extensively used in playing on the G string, but here too it is narrow and by no means continuous. See, for instance, Spohr’s annotations in the middle section of the Adagio from Rode’s Seventh Violin Concerto in his Violinschule, p. 209. All in all, her recordings indicate that she was affected extraordinarily little by the stylistic changes that had occurred in vibrato usage during her career.

Portamento

Another contributing factor to ‘unhealthy music-making’, in Joachim’s opinion, was tasteless portamento. This clearly did not mean that he advocated the total suppression of portamento, and his recordings show that he used it as a normal concomitant of legato position changing, although perhaps introducing it rather less frequently than some of his contemporaries might have done in that repertoire. As with vibrato, he was concerned that it should be executed ‘correctly’ and used in the right places. In fact, portamento was evidently seen by Joachim as a more important, indeed more indispensable aspect of expressive performance than vibrato, and it received considerably more attention in the Violinschule, where its discussion, taking up six and a half pages in the second volume, preceded that of vibrato. In the essays in the third volume, Moser stated that ‘portamento stands in the first rank’ among the vocal effects that can be recreated on the violin (III, p. 8).

Relevant technical and aesthetic aspects of portamento have been discussed in detail elsewhere (Brown, Classical and Romantic, pp. 558-587). It is sufficient here to reiterate that audible shifting within and sometimes between bowstrokes was an inevitable outcome of nineteenth-century teaching on position changing, but that the location of a position change was expected to be selected on the basis of its musical aptness, that the intensity (bow pressure) and speed of the shift should be determined by musical considerations, and that certain types of portamento were regarded as tasteless by some authorities. Warnings about the ‘improper’ execution of shifts were already made by Spohr, but the manner he condemned, in which the slide was made with the finger that stopped the target note rather than that which was used for the starting note (Spohr, Violinschule, p. 120), seems to have been used with growing frequency during the second half of the century. It was commented upon in Germany and England from at least the 1880s, often specifically referred to as ‘French’ portamento. Hermann Schröder, for instance, deplored it in 1889 as a ‘perverted mannerism’ deriving from French players, but now employed in Germany (Schröder, Die Kunst des Violinspiels, p. 33); and in 1898 John Dunn observed that this type of portamento was ‘a striking mannerism common to many, but not all, players of the modern French school’ ( John Dunn, Violin Playing, (London, 1898), p. 31), while Flesch in 1924 wrote that ‘among the great violinists of our day there is not one who does not more or less frequently’ use it’ (Carl Flesch The Art of Violin Playing, p. 30). Early recordings provide a wealth of information about the employment of portamento during the first half of the twentieth century, confirming not only that the use of ‘French’ portamento in various manifestations became increasingly widespread during the early decades of the century, but also that portamento as a whole was still extensively employed in string playing and singing until at least the 1930s, after which it rapidly came to be regarded as a bad habit and has been largely eliminated from more recent performing practice. (The suppression of portamento went hand in hand with changes to fingering practices.) As part of the process by which portamento became discredited during the twentieth century its origins and function were forgotten. Few musicians of the present day are aware that its employment as an indispensable expressive practice in string playing dates back to the late eighteenth century, for along with other old practices, such as piano arpeggiation and dislocation, the musical generation that rejected it seems to have believed it to be a tasteless perversion indulged in by their recent predecessors.

In all but one instance (discussed below) the execution of Marie Soldat’s portamentos in the 1926 recordings is entirely within the parameters of good taste that were laid out in Spohr’s Violinschule. In this respect, her treatment of the Spohr Adagio is particularly revealing. There is good reason to believe that it was one of her regular repertoire pieces from an early stage. She played it during her first visit to Britain in 1888 and at a concert in Edinburgh was praised for performing it ‘with a sweetness and purity of expression that took the house by storm’ (The Musical World, 14(1888), p. 276). In 1896 the critic of the Athenaeum remarked that in this piece ‘her style singularly resembled that of Herr Joachim’ (The Athenaeum , 3604(1896), p. 722). It also appeared in the programme of a concert given by her quartet in Olmütz on 6 January 1896 (programme in private possession). In her recording Soldat mostly seems to have employed the fingering marked by Spohr, and executed the portamento implied by it, but she occasionally departed from his fingering to achieve an additional portamento effect (she executed twelve portamentos in the first sixteen bars, all but two of which were implied by Spohr’s fingering).

Portamento, though still an integral aspect of her expressive language, is less prominent in Beethoven’s Romance in F, where its use is not so integral to the expression, although all her position changes within legato passages are audible (as in Joachim’s playing) and, in most cases, clearly chosen for their musical aptness. Prominent portamento is even less evident in the first movement of Mozart’s A major Violin Concerto, suggesting her understanding that the embellishment was more appropriate in some repertoires than others. This too was surely a legacy of her study with Joachim. (Karl Klingler’s writings make it clear that this kind of stylistic awareness was integral to the Joachim tradition. See Karl Klingler: “Über die Grundlagen des Violinspiels” und nachgelassene Schriften. ed. M. M. Klingler and A. Ritter (Hildersheim, Olms, 1990).) Soldat’s performance of the Largo from Bach’s C major Sonata for solo violin, therefore, is somewhat unexpected. Although a reviewer in 1897 had observed that Marie Soldat ‘played two movements from Bach’s suite in E, quite in the Joachim style’ (The Musical Times,38(1897), p. 20), her recording of the Largo contains much more portamento than Joachim used in his 1903 recording of the Adagio from the G minor Sonata (although not more than Rosé, for instance, employed in that Adagio). The character of Soldat’s Bach performance seems considerably more impassioned than Joachim’s. It is unclear what edition she may have learned the sonatas from, since Joachim’s own edition did not appear until 1908, but it is likely that it was Ferdinand David’s; several of the portamentos suggested by printed fingerings in that edition occur in Soldat’s performance.

In any case, since a particular passage can be played with various fingerings, she also introduced portamento in places where none is implied in the fingerings indicated in the editions that would have been available to her. Her performance of Schumann’s ‘Abendlied’ is also rich in portamento, although the piece could easily have been played with very few position changes; it contains some twenty-three portamento effects (many, however, quite subtle and unobtrusive) in twenty-nine bars, creating an extremely expressive cantabile performance. All of these are of a kind that might have been approved by Joachim, although whether he would have introduced so many and in the same places cannot be determined. Joachim certainly used fewer portamentos in the 1903 recording of his Romance in C (the transcription in my book Classical and Romantic Performing Practice (pp. 450-454) marks only the most prominent portamentos; there are, for instance, seven quite audible position changes in the first sixteen bars although I indicated only three of them.), but it may be argued that the character of that music invites them less than the much slower-moving and more intense ‘Abendlied’. The evidence of portamento fingering in Spohr’s Violinschule, especially in the Adagios of Rode’s Seventh Concerto and his own Ninth Concerto suggests that mainstream practice in the German tradition allowed more frequent portamento in particularly expressive contexts than the rather puritanical Joachim might himself have employed.

Soldat’s performance of the Bach-Wilhelmj ‘Air on the G string’ stands apart from her other recordings, all of which belonged to Joachim’s repertoire , not only because it is a piece Joachim detested (Flesch, Memoirs, p. 48 footnote), but also because in performing it, as well as using very frequent vibrato, she employed some ‘French’ portamento. Perhaps her sense of style and tradition, which determined the use of classic portamento elsewhere, permitted her to use this much criticised portamento in the context of a piece that belonged to a different tradition. Wilhelmj, a favourite pupil of Ferdinand David (whose playing and teaching was seen as combining his inheritance from Spohr with aspects of Franco-Belgian practice; see Ferdinand David as editor), seems to have had more in common with the Franco-Belgian tendency than the German. A sense of stylistic aptness similar to Soldat’s in this recording may explain Joachim’s use of this French portamento in his recording of Brahms’ First Hungarian Dance, presumably because it was also seen as a characteristic of Gypsy fiddling.

Bowing and phrasing

Styles of bowing can scarcely be discussed on the basis of recordings alone, for it is frequently impossible to link the sounds heard in a recording to specific bowing types or movements of the arm. The implications of Moser’s strictures about the poor use of the bow by Franco-Belgian musicians, therefore, are more difficult to investigate through recordings. As with questions of vibrato and portamento usage, the necessary comparison of written texts, annotated editions, iconography, and recordings has yet to be undertaken extensively and systematically enough to achieve reliable conclusions. One aspect of the physiology of bowing, however, that is abundantly clear from documentary sources, is that a fundamental change in teaching about the position and action of the right arm and hand occurred during the first half of twentieth century. Standard instructions from the middle of the eighteenth to the early twentieth century, illustrated graphically and photographically in numerous violin methods (see my article ‘Physical parameters of 19th and early 20th century violin playing’), demanded a lowered right elbow, quite restricted movement of the upper arm, very extensive flexibility of the wrist between the point and heel of the bow, and, in most cases, a bow grip in which the fingers lay close together and the stick rested between the first and second phalanxes of the index finger. In the closing section of the Geschichte des Violinspiels Moser had praised Karl Klingler’s fidelity to the Joachim principles in respect of bowing, but ten years later Carl Flesch criticised Klingler’s bowing as ‘still dominated by the fallacious theory of the lowered upper arm and “loose” wrist’ (Flesch, Memoirs, p. 250). In his Art of Violin Playing in 1924 (just three years after the appearance of Klingler’s Grundlagen des Violinspiels) Flesch rejected the old German method of holding the bow declaring that ‘the majority of contemporary violinists have, however, already turned their backs upon it’, and adding that the ‘the newer Franco-Belgian, as well as the Russian manner of holding the bow already control the field absolutely and incontestably’ (Flesch, The Art of Violin Playing, p. 54). He favoured the latter, which he attributed to Auer. If we cannot, in the present state of knowledge, identify the progress and consequences of these changes more precisely in early recordings, we can certainly hear the results of the older method in the recordings of Joachim himself and his pupils Klingler and Soldat.

There is good reason to believe that Soldat’s bowing was broadly faithful to Joachim’s method, not least because of the numerous reviews that referred to the similarity of their playing style. Her mastery of the bow was acknowledged, for instance, in a review from 1909, which remarked upon ‘her beautiful bowing being especially noteworthy’ in performances of three Beethoven Violin Sonatas’ (The Musical Standard, 28(1907), p. 345). Among the features frequently mentioned in written accounts was its vigour. This can be heard distinctly in her recordings, in the first movement of Mozart's A major Violin Concerto, the middle section of Beethoven’s Romance, and Bach’s prelude from the E major Partita BWV 1006.

A review of her performance in Brahms’ B major Piano Trio and Bach’s E major Partita by the distinguished Manchester music critic, Samuel Langford, in 1908 provides an interesting insight. He observed that she

plays Brahms to perfection, and did gloriously in the Trio; she also gave to older music – the E major sonata by Bach for violin alone – a Brahmsian breadth and vigour. We have never before heard the Sonata played so vigorously throughout, and we certainly prefer the opposite method adopted by Señor Casals, of finding all the lightness that is possible in Bach. But whatever could be done by beautiful tone, intelligent phrasing and natural dignity to add force to her method Madam Soldat-Roeger did admirably. She might have convinced many that her style, too, was right, but we were not of the number. [The Manchester Guardian, Nov. 2, 1908, p. 8. The reference to Casals is interesting because he and Marie Soldat played piano trios together, with either Leonard Borwick or Fanny Davies, between 1909 and 1913.]

This style of bowing for continuous passages of faster-moving notes is clearly related to the type of détaché described in the Paris Conservatoire Méthode of 1803, Spohr’s Violinschule and many later German treatises, including the Joachim and Moser Violinschule. In his Geschichte des Violinspiels Moser stressed the importance of this bow-stroke; rejecting F. A. Steinhausen’s contention that the older teachers dealt only with the use of the wrist, he insisted:

absolutely to the contrary, not only Joachim, Böhm and Rode, about whom we definitely know it, but probably also their predecessors Viotti and Pugnani etc., put much more emphasis on the cultivation of the elbow joint to produce a spirited management of the bow, because without its looseness a free forearm stroke, the most important for playing passagework, can certainly not be achieved. (Ganz im Gegenteil haben nicht nur Joachim, Böhm und Rode, von denen wir es positiv wissen, sondern wahrscheinlich auch schon ihre Vordermänner Viotti und Pugnani usw. Zur Erzielung einer schwunghaften Bogenführung ungleich mehr Nachdruck auf die Kultur des Ellbogengelenks gelegt, weil ohne dessen Lockerheit ein freier Unterarmstrich, der wichtigste für das Passagenspiel, gar nicht zu erreichen ist. ’ [Moser, Geschichte, p. 555.]

During the early twentieth century this bowing style was rapidly being displaced by the ‘lighter’ type of bowing referred to in Langford’s review, which involved quite different movements of the arm and hand. Although springing bowings of various types were certainly employed by Joachim and his pupils, they were equally certainly not employed in the same way or in the same contexts as nowadays.

Another aspect of Soldat’s bowing can be heard particularly in the legato sections of the Beethoven Romance, Schumann’s ‘Abendlied’, and Spohr’s Adagio. These pieces reveal her remarkable cantilena, in which the bow changes are often almost undetectable. Such extreme smoothness of bowing is seldom encountered to this extent in recordings by younger performers, who could undoubtedly have achieved it, but seem not to have been concerned to do so. The Adagio also demonstrates her perfect command of the ‘Spohr’ or ‘firm (festes)’ staccato, executed with remarkable delicacy and precision.

Rubato

Joachim was famed above all for his incomparable ability to bend the music expressively within an essentially constant pulse. Both Karl Klingler’s and Marie Soldat’s recordings present many examples of similar qualities, which, combined with other stylistic features, must have played a part in fostering the widespread opinion that their playing was very much in his style. This was not, however, merely a peculiarity of the performing style of Joachim and his pupils at the beginning of the twentieth century; players with quite different backgrounds employed related types of rubato, for instance Ysaÿe and Flesch, but in ways that were different from Joachim’s. (This can be easily observed subjectively. A more empirical investigation of different types of rubato in early recordings is still to be undertaken.) The Joachim style of rubato is closely paralleled, however, in the piano playing of Carl Reinecke (1824-1910), suggesting a connection with Leipzig traditions stretching back at least to Mendelssohn’s time. Joachim specifically referred to Mendelssohn’s ‘elastic management of time as a subtle means of expression’ (Violinschule, III, p. 228); and Spohr clearly described this kind of rubato in his 1833 Violinschule (p. 119). Particular aspects of the rubato heard in Mozart and Beethoven recordings by Klingler, Soldat, and Reinecke, particularly the unequal performance of slurred figures in which the elongation of the first note is compensated for by hurrying the subsequent notes under the slur, appear to represent the preservation of eighteenth-century traditions. (See Clive Brown ‘Performing Classical repertoire: the unbridgeable gulf between contemporary practice and historical reality.’ Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis XXX (2006) (Winterthur, Amadeus Verlag, 2008), 31-44, and ‘Leopold Mozart’s Violinschule and the performance of W. A. Mozart’s violin music’ in Cordes et claviers au temps de Mozart / Strings and Keyboard in the Age of Mozart ed. Thomas Steiner (Lausanne, Peter Lang, 2010) pp. 23-49). All of them also played dotted figures freely, often over-dotting in a manner that recalls Leopold Mozart’s advice, but was also an aspect of Brahms performing practice, as a reviewer in 1933 pointed out with reference to Soldat’s flexible performance of the dotted figures in the second movement of the G major Violin Sonata op. 78 (The Musical Times,74(1933), p. 548)

Soldat’s masterly performance of the Adagio from Spohr’s Ninth Concerto represents a freer style of tempo rubato that corresponds closely to Spohr’s precepts and gives a very strong impression of preserving the style of performance its composer envisaged. Either Pott, whose years of study with Spohr were close to the composition of the Ninth Concerto, or Joachim, who had heard and admired Spohr’s playing, or perhaps both of them, may have been responsible for coaching her in the composer’s style of performing this music. Comparison of Soldat’s performance with accomplished modern performances of the same piece, in which, however, it is played more or less strictly in time, with continuous vibrato, scarcely a hint of portamento, modern bowing, and far from seamless legato (Ulf Hoelscher CPO 999 232-2 and Christine Erdinger Marco Polo 8.223510); Erdinger plays the Spohr staccato, marked with dots under a slur, with separate bows, creating an entirely different effect from the one intended, while Hoelscher’s slurred staccato is crude in comparison with Soldat’s pearl-like execution of that characteristic 19th-century bowstroke. This reveals how fundamentally different such music becomes when played with the styles of tempo rubato, ornamental vibrato, expressive portamento exquisite phrasing , and distinctive style of bowing that were cultivated by Spohr, Joachim, Soldat and other violinists in the nineteenth-century German tradition.

*

It is clear from her recordings that Marie Soldat was an artist in her own right, not merely an epigone of Joachim. At the same time, however, it is evident that, more perhaps than any other recorded violinist, her performances preserved many of the essential features that led her to be described as a faithful student of the Joachim School. It is also credible that she was directly linked through August Pott to a Spohr tradition, and tempting, indeed plausible, to imagine that her manner of playing the Adagio from Spohr’s Ninth Concerto would have seemed perfectly idiomatic in almost every respect to its composer.

For musicians who aspire to perform 19th-century music, and perhaps also that of the late 18th-century, in a manner that more closely reflects the expectations of its composers, Soldat’s recordings offer many fascinating perspectives in all the areas examined above. Although modern or period violinists may not wish to play Bach in the 19th-century manner created by Ferdinand David, Joseph Joachim and their contemporaries, there is every reason to believe that in repertoire from Mozart to Brahms, her way of playing is far closer to a stylistic world with which those composers would have been familiar, than any kind of modern performance we are likely to hear at present, ‘historically informed’ or not.