CHASE

CHASE

W. A. Mozart: Violin and Viola Duos — the 'Uppingham' collection - Part B

TITLE PAGE, Abstract, Acknowledgements, Citation

Part A: INTRODUCTION (David Milsom & Clive Brown)

Part B: FERDINAND DAVID’S EDITION IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT (David Milsom)

Part C: PERFORMING FERDINAND DAVID’S REALISATION OF THE MOZART VIOLIN & VIOLA DUOS (David Milsom & Clive Brown)

Part D: EXPERIMENTAL RECORDINGS (Clive Brown – violin; David Milsom – viola)

Part E: CONCLUSIONS (David Milsom)

Part F: LIST OF REFERENCES

________________________________________________________________

Part B: FERDINAND DAVID'S EDITION IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT (David Milsom)

B1. Early Editions of the Duos K. 423 & K. 424

As has been established for some considerable time, the status of the first published edition of the duos is somewhat problematic. The first published edition (Artaria, 1792: see Table 1 below) appears to differ substantially from the autograph manuscript, most notably in terms of a decorated reprise of the passage at bars 43-45 of the middle movement of the G-Major Duo, but also in terms of numerous changes to dynamics, articulation markings and slurs/phrase marks. Modern scholars, including Ulrich Drüner in his foreword to the Amadeus edition of 1980, suggest that the Artaria edition was based upon a later revision by Mozart himself, Drüner positing in respect of the Artaria edition that:

It is possible that he himself instigated the printing, but there is no proof; neither can one ascertain what source the first edition was based on. […] Whilst the authenticity of these variants cannot be conclusively proven, it must be noted that the variation between bears [sic] 38-41 and 42-45 in the slow movement of KV 423 is “Mozartian” and should be preferred in performance. The exact repetition of these passages in the autograph is rather surprising in Mozart and it can be conjectured that the variation in the first edition is by Mozart himself. [Mozart/Drüner, 1980: IV]

Drüner makes reference Aloys Fuchs’ annotation of the 1783 autograph manuscript in 1850 in which Fuchs came to the conclusion that the autograph could be considered ‘as the 1st sketch of the Composition.’ What seems to be clear, however, is that the editions of the period 1792-1815 consulted for this project were based closely on the Artaria edition, and discrepancies from it are relatively small-scale/localised, possibly implying changing performing practices, but more persuasively simply for matters of commercial expedience – this relates in particular to some of the more ‘detailed’ markings of phrasing/slurring which might be seen as attempting to create a more complete set of indications for the preparation of performance. As one might expect of editions from this time, those of 1792-1815 are comparatively crude by modern standards (there are scarcely any fingering markings and no bow indications other than slurs), and thus David’s edition is the first with such relatively comprehensive performance information. For the purposes of this investigation, David Milsom has consulted the following editions from copies obtainable in the British Library [Table 1]:

Table 1: Published editions 1792-1815 from British Library Collections

| PUBLISHER | PLACE | DATE | BL CATALOGUE REF. |

| Artaria | Vienna | 1792 | g.218.d.(6.) |

| Hummel | Berlin; Amsterdam | 1792 | h.405.i.(6.) |

| André | Offenbach sur le Mein | 1793 | H.3690.II |

| Longman & Broderip | London | 1800? | Hirsch M.1429 |

| Hummel | Berlin; Amsterdam | 1802 | Hirsch IV.69 |

| Böhme | Hamburg | 1805? | Hirsch M.1081 |

| Broderip & Wilkinson | London | 1805? | R.M.14.f.22.(16.) |

| Clementi, Banger, Hyde, Collard & Davis | London | 1810? | h.405.q.(4.) |

| Monzani & Hill | London | 1815? | g.421.(1.) |

B1. a) Published Editions 1792 – 1793

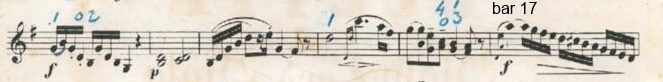

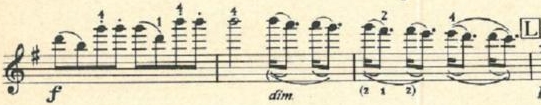

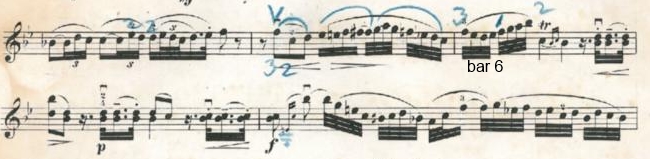

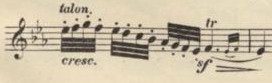

Three of the editions consulted were produced in quick succession following the Artaria edition in 1792. The Andre edition of 1793 appears to be a plagiarised version of the 1792 Artaria edition and is virtually indistinguishable. The 1792 Hummel edition is, however, more interesting and appears to indicate a rather more detailed scheme, especially as regards phrasing and articulation, particularly in respect of K. 424. K. 423 is substantially as the Artaria edition (and all of the editions considered here replicate the substantial revisions to bars 43-5 of the violin part in the slow movement of K. 423 as well as bars 17 and 19 of the viola part of the slow movement of K. 424) but the Hummel edition creates a more complex and articulate approach to running 1/32 figures, as can be seen in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Bars 24-25, movement I, K. 423 – Comparison of Artaria (1792) & Hummel (1793)

The slow movement has fewer changes to the Artaria edition in both parts, although in bar 7 in the violin part the first eight 1/32-notes split the slur of the Artaria edition into two groups of four, the p marking in the Artaria edition at bar 12 is omitted, and wedges, used throughout the Hummel edition, are added to the separate 1/16-notes in bar 26 of the violin part.

The Finale sees a number of differences, although, as elsewhere, not all of these appear to be musically significant and represent perhaps changes of presentation, such as the annotation of the trill in bars 26 and 45 in the violin part, or the change from f to mf at bar 27. Indeed, the Hummel edition replicates the fingering in bar 182 (the only instance of fingering being indicated in these editions) which suggests perhaps that the edition was prepared not only in the light of the Artaria edition (which is obvious given the fact that it replicates the substantial notational changes of the Artaria edition compared to the autograph score) but that it was, to a certain extent, based upon it.

Otherwise, the editorial approach can appear more detailed and thoughtful. Bar 67 slurs all eight 1/16-notes in one bow, unlike the Artaria edition which splits the slur into two groups of four; in this respect the Hummel edition might be seen as a rationalisation or correction of the Artaria edition which is inconsistent in this respect. It is in the viola part where more interesting differences emerge, presaging perhaps the larger number of variations between these editions found in K. 424. The accompanying figure at the start of the Finale is left unmarked as separate bows in the Artaria edition (and indeed, the 1783 Autograph) but the Hummel edition creates a more intricate scheme [Figure 2]:

Figure 2: Bars 1-4, movement III, K. 423 – Hummel (1793)

On the repeat of this material from bar 58, it is interesting to note that bars 5 and 62 differ, bar 5 being slurred in pairs, and bar 62 in a group of four. At bar 40, the triplet 1/8-notes, also left unmarked in the Artaria edition, admit the following treatment [Figure 3]:

Figure 3: Bar 40, movement III, K. 423 – Hummel (1793)

These differences imply perhaps a correction and augmentation of information in the Artaria edition – there are few places in which the two editions contradict each other and in many ways the Hummel edition might be seen as a more detailed approach to the realisation of the work. Certainly, it appears that the realisation of running 1/16-note passages might give rise to a degree of personalisation by performers in this period. Ornamentation – the sine qua non of earlier 18th-century style – appears to have remained part of late-18th- and 19th-century practice and, as the authors have shown in respect of editions of Viotti's Violin Concerto no. 22, even editors as late as Joseph Joachim could provide texts ornamented by means of additional notes (as in the slow movement of this concerto – including, of relevance here, Ferdinand David’s edition of it) [see Brown & Milsom, 2006)]. On a smaller scale (but still as part of a cognate philosophy) it seems clear that an ornamented way of playing passages in shorter note values (groupings of notes under slurs, etc.) was evident in the Classical and Romantic periods and, as Clive Brown suggests in respect of the Beethoven Violin Concerto, such matters could be left to the individual discretion of the player: ‘There is every reason to believe that although Beethoven was quite careful to indicate slurs in the orchestral string parts, he left the slurring and articulation to be determined by the soloist.’ [Beethoven-Brown, 2012: 12.]. Whilst most of the differences in K. 424 (as in K. 423) relate to different slurred groupings, there are some other discrepancies: in bars 93, 95 and 97 of the viola part (first movement Allegro) the ‘fzp’ markings in the Artaria edition are replaced by the ‘sfp’ marking found in the 1783 autograph (possibly a difference of editorial/semiotic ‘style’ rather than intended aural effect) whilst at bar 19 in the viola part of the Andante movement, the Hummel edition replicates the Artaria edition’s notes (which are a substantial change from the 1783 autograph – see Figure 4) albeit adjusting the final note to a g'.

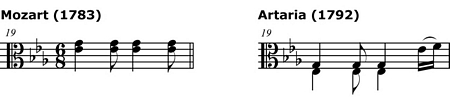

Figure 4: Bar 19, movement II, K. 424 – Comparison of Mozart (1783) & Artaria (1792)

In Bar 25 of the Artaria edition Finale violin part, the eighth and ninth notes are given as B♭ and C♮, differing from the autograph (which has an apparently more correct A♮ and B♭), although the Hummel edition appears to correct what appears to be an error; at bars 88-89 there is also an apparent ‘error’ in the Artaria edition but this time this is replicated by the Hummel edition as well [Figure 5]:

Figure 5: Bars 88-89, movement III, K. 424 – Comparison of Artaria (1792) & Hummel (1793)

It is also interesting to note that, in the violin part, bars 26-7 are identical in the Artaria and Hummel editions, including the curious separate bow realisation of 1/8-note beat 4 in bar 27 [Figure 6]:

Example 6: Bars 26-27, movement 2, K424 – As realised by Artaria (1792) & Hummel (1793)

Otherwise, differences between the Artaria and Hummel editions exist in terms of more detailed, intricate and implicitly specific markings of slurs and articulations.

B1. b) Editions 1800-c.1815

Editions in the British Library collection from 1800 up to c.1815 appear to be based closely on the Artaria edition, or subsequent versions of it in later editions. The 1802 Hummel edition is identical to that of 1792, sharing the same plate number. The 1805 Broderip & Wilkinson edition, for example, is very substantially as Artaria, apart from some missing slurs (as at bar 8 of the Andante in the violin part of K. 424) in a rather crude engraving in which many such discrepancies might well be simple errors. The 1815 Monzani & Hill edition of K. 423 contains some small variations in the violin part some of which seem to be errors/omissions (such as missing slurs in the violin part in bar 19 of the first movement) and some of which seem to be small-scale differences, such as replacing the forte marking at bar 7 of the first movement violin part with sf and following this with a crescendo marking in the next bar. The second movement of the violin part is almost identical to Artaria, whilst the passage at bars 84-8 suggests some differences [Figure 7]:

Figure 7: Bars 84-88, movement I, K. 423 – Comparison of Artaria (1792) & Monzani & Hill (1815)

The reasoning behind these changes compared to the Artaria edition is difficult to account for, since the viola part is practically indistinguishable from the Artaria edition. Certainly, there is little here, as in the other early editions after 1800, to suggest that any of these editions are based on a source other than Artaria, and in this latter case in particular it seems plausible that such differences as do exist do not so much represent substantial differences of approach to these works or their realisation but are, simply, individual differences, many of which (given the primitive nature of these documents) may simply be errors.

B1. c) Ferdinand David’s edition (Senff, c.1866) in the Context of Early Published Editions

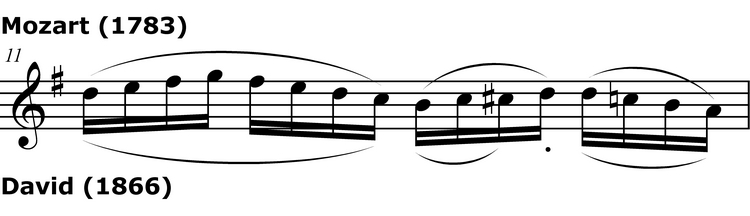

Whilst it is possible that David knew of and consulted the autograph score of 1783 (the score is recorded as being in Mannheim at the time of the compilation of the Kochel catalogue in 1860-62) it is difficult to draw any clear conclusions – David’s edition (including realisation of rhythm in bars 38, 39 and 42 of the second movement violin part and the use of the embellished repeat in bars 43-5) appears to be based on the first published edition by Artaria of 1792 with markings that, as other scholars have suggested, might comprise Mozart’s own revisions in comparison to the hastily-written 1783 manuscript. (It will be noted, however, that there has yet to be any evidence of a revised Mozart manuscript on which the Artaria edition is based, so this matter remains conjectural). Nonetheless, there are a number of places in which David, whose edition is in many ways significantly independent of other editions, suggests knowledge of the 1783 manuscript – something that seems unlikely in the case of the early editions up to 1815, as established above. In K. 423 (violin part), bar 11 replicates the 1783 edition, not that of 1792 [Figure 8]:

Figure 8: Bar 11, movement I, K. 423 – Comparison of Mozart (1783) & David (1866)

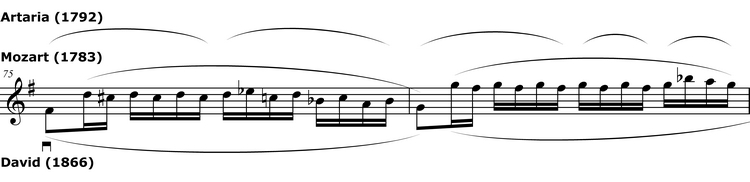

Meanwhile, David’s bowing scheme for bars 75-76 seems similar to the autograph manuscript, and certainly closer to it than to the Artaria edition [Figure 9]:

Figure 9: Bars 75-76, movement I, K. 423 – Comparison of Mozart (1783), Artaria (1792), & David (1866)

In the second movement of K. 423, David’s slurs in bars 24-25 more closely resemble those of the 1783 autograph, whilst the dynamics at the end, especially in the viola part, appear strikingly similar [Figure 10]:

Figure 10: Bars 24-25, movement II, K. 423 – Comparison of Mozart (1783) & David (1866)

A similar pattern emerges in the B♭ Duo. The first movement (particularly the crayon adaptations) suggest at least a working knowledge of the 1792 edition, whilst from bar 8 to the end of the Adagio, the longer slurs in David’s edition align more closely with the 1783 edition. In bars 52-3 the slurred staccato found in both the 1783 and 1792 editions is also found in David’s, showing that he is likely to have known at least one of these sources, whilst superficial similarities in the realisations of bars 74-6 may, again, imply a knowledge of the 1783 edition.

Equally circumstantial is the issue of the 'sfp' signs at bar 93 in this movement. Later editors, from (and including) Schulz use this sign rather than the 'fzp' of the 1792 edition; this might again be a matter of typesetting coincidence or might suggest that, by the late 19th century, Mozart’s 1783 autograph was rather better known and had been viewed. With David’s edition the matter is less clear. David places 'sf' in the centre of a messa-di-voce – this may or may not indicate a knowledge of Mozart’s earlier source, or of course, early editions (such as Hummel) which use the ‘sfp’ marking. Nonetheless, the printed slurs in the second movement of K. 424 at bar 23 seem very closely related to the 1783 edition, whilst the two-bar slur in the viola part in bars 195-6 also replicate the 1783 autograph.

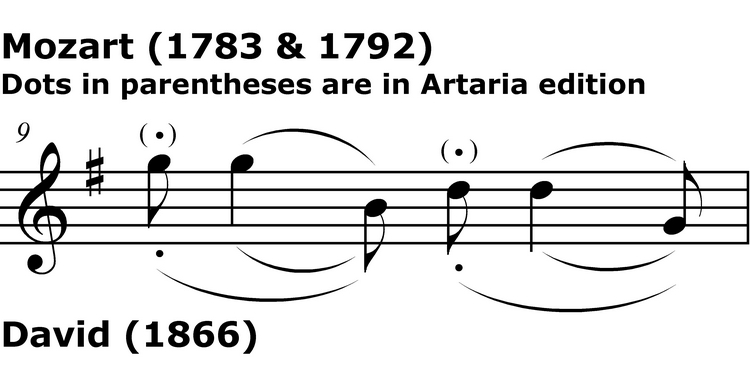

Whatever the parity or otherwise of David’s edition with either the 1783 autograph or 1792 edition, what is immediately noticeable is the independence (and indeed detail) of David’s edition, which is, in turn, further developed in the blue crayon markings. Some of the differences between David and the earlier editions are perhaps inevitable – splitting some of the longer slurs (which, as Ulrich Drüner suggests, are probably better seen as phrase marks rather than literal bowings [Mozart/Drüner, 1980: III]) – others constitute the kind of editorial activity that became common in the 19th century in terms of adapting and augmenting dynamic markings (including subtler shadings than generic values of forte and piano, as well as crescendo and diminuendo markings, and accentual markings, such as sf), adding fingerings (in some cases for technical reasons, in others for more unambiguously expressive ones), and bowings. Some bowings constitute actual changes to Mozart’s writing; in other cases they are practical technical solutions, such as ‘hooking-in’ figures that are difficult to execute as written because of unequal division of the bow – compare, for example, Mozart’s slurs (as indicated in both the 1783 autograph and 1792 Artaria edition) in bar 9 of the G-Major Duo, movement I (violin part) with David’s ‘over-slurring’ which implies a retention of the phrasing, but in the same bow for technical convenience [Figure 11]:

Figure 11: Bar 9, movement I, K. 423 – Comparison of Mozart (1783) & David (1866)

David thus made a number of independent changes. In many cases, these can be seen as augmentations – providing, as it were, his ‘version’ of the music for performance, with subtleties of dynamic inflection and indeed bowing style included. There is no attempt made, as there would be in a modern edition of such canonical repertory, to differentiate between David and Mozart; nor would one expect an edition of this period so to do, were it not for the generally scholarly bearing of Leipzig editors and, for example, the care with which David could prepare editions. His edition of the J.S. Bach Solo Sonatas and Partitas [Bach/David, 1843] has parallel notation giving Bach’s ‘original’ against his own realisation of it: a remarkably prescient approach to editing historical material. This might be said to suggest that Mozart was not considered in the same way – as if David were part of a continuing classical tradition, whereas J.S. Bach was treated with perhaps greater reverence because his music had ceased to have this connection.

A modern attitude of ‘reverence’ to Mozart’s (canonical) text is implied by Ulrich Drüner:

If one interprets the original phrase marks as bowing marks, their frequently considerable length makes if [sic] difficult to produce the intensity of tone needed in public performance. […] Personal marking is therefore necessary, but should be done with the greatest care: the subdivision of overlong slurs is often unavoidable; however, as soon as one tampers with shorter slurs one is interfering more or less seriously with the original phrasing! [Mozart/Drüner, 1980: III]

Drüner’s position here seems reasonable from a 21st-century viewpoint, and certainly David’s edition does constitute ‘tampering’. But whether this is based upon ignorance, ‘improving’ the work ideals (Mozart's 'intentions', perhaps), or, as seems more likely, a freer attitude towards the musical text (which may well have been within Mozart’s own expectations of how his music would be played) is difficult to gauge. Whether David’s markings here represent an up-dating of Mozart’s musical language for the mid- to late-19th century, or whether, in a tradition that made much of its claims to defend and perpetuate the performance values of the Viennese classical style, they represent some tangible connection with the first generation of Mozart performance is difficult to ascertain. David’s process of adding to and adapting Mozart’s markings, though, should not be seen as simply contradicting Mozart’s apparent expectations of performance, particularly at a time in which freedom and spontaneity in the performance act was not only inevitable, but actively encouraged as the basis of good artistic rendition.

B2. Ferdinand David’s Edition in the Context of Representative Later Editions

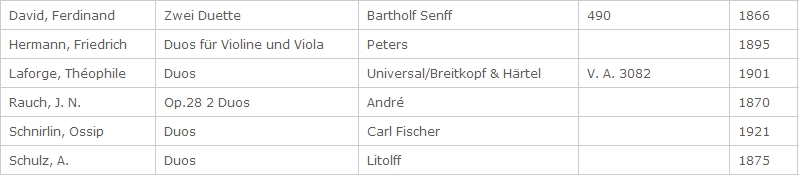

The CHASE project houses a number of annotated editions of the Mozart Duos [Table 2; see also here] which make for interesting comparison with David’s Senff edition (which, at the time of writing at least, would appear to be the first edition to be marked in the modern manner, with bowings and fingerings).

Table 2: Mozart Duos K. 423 & 424 – editions on the CHASE website

Rauch’s edition (1870) seems to act largely independently of David’s, although there are a number of similarities, mainly in places where David’s additional markings (such as fingerings) are relatively straightforward. This edition is notably simpler in terms of dynamics than the others, with closer correspondences to the Artaria edition. The most influential edition appears to have been that of Schulz (1875), which is the basis of many of the markings in the later editions. It is curious to note that the Friedrich Hermann edition (1895) is based mainly, it would seem, on Schulz, and not Hermann’s former mentor, David.

With the exception of the edition by Théophile Laforge (1863-1918) for Universal, dated 1901 (which, in all probability was prepared in the 19th century) the only unambiguously 20th-century edition to be included here is that of Ossip Schnirlin (1873-1939) in his Der Neue Weg [Schnirlin, 1921] – a work dedicated to ‘teaching’ violin repertory by means of annotated excerpts (and, as here, complete works). The preface to Part 2 suggests that Schnirlin intended there to be further additions to the series [‘I have compiled a chronologically grouped collection of all the difficult passages for 1st and 2nd violin and 1st and 2nd viola which occur in the most important works throughout the entire range of chamber music.’], but other instrument/part-specific volumes do not seem to have been published – no evidence of them is known today, and the project may never have been completed. Schnirlin was a pupil of Joseph Joachim and a prolific editor of music for Simrock (a publisher with obvious Brahms/Joachim associations), including ‘augmentations’ of Joachim’s editions (such as the Brahms-Joachim Hungarian Dances [Brahms-Joachim/Schnirlin, 1932]) and potentially fascinating and important editions of music in a manner apparently similar to Joachim’s practices but which Joachim did not edit (including the Brahms violin sonatas – see, for example, Sonata No. 1 in G Major, op. 78 [Brahms/Schnirlin, 1926]. Schnirlin’s status appears to have been that of a latter-day disciple of the Leipzig tradition, rather perhaps in the manner of Karl Klingler (1879-1971) or Marie Soldat (1863-1955).

When viewing these editions, the first thing one notices is the marked similarity between those by Schulz, Hermann, and Laforge. This is curious given the chronological spread of these copies, and indeed the rather ‘separate’ status of Laforge from this Leipzig-based tradition. Equally, it is curious that David’s edition has relatively few correspondences with these later editions – there are numerous differences of bowings, fingerings and dynamics (the three parameters considered in the bibliographic studies in this article). Rauch’s edition, only four years after David, seems nonetheless to have been quite independent of it. The next edition in chronological order here is Schulz, who, whilst ‘explaining’ some of David’s signs (by replacing some of David’s dots above notes with lines) also significantly simplified David’s detailed approach to editing. It is also simpler than Rauch’s edition which can be, by turns, both complex (especially in respect of bowings) and relatively simple (as in the case of dynamics). Whilst Schulz does reflect some of the ideas of David and Rauch, much of the detail of his edition is different. This said, it is notable that all of the editions here are consistent with performing practices which one associates with the period (and David specifically – see section C2) – this includes bowstrokes often implicitly (or explicitly) taking staccato notes on the string in the upper-half of the bow, fingering systems that allow for (or even encourage actively) the portamento, and dynamic schemes that seek to create varied and expressively-colourful interpretations.

The inter-relationship of these various editions, of course, gives rise to questions relating to editorial process at this time. Whilst any present-day editor would perhaps base their work on the Neue Mozart Ausgabe edition [Mozart, 1955-1991] we do not know how these editors proceeded. It seems likely that they referred to an early edition (possibly that by Artaria), but equally, the similarities between them suggests that they were aware of each other’s work. It seems probable, differences aside, that the three editions by David, Rauch and Schulz, published in a close period entailed awareness of previously-published editions in this group, whilst editions after Schulz seem to reflect similarities with his edition that go beyond mere coincidence. The relatively few references to David’s edition are puzzling in that, given his high status as a member of this tradition, it is curious that his work was not more widely referenced. Thus, David’s edition has perhaps a dual status – on the one hand, it is the first edited/annotated edition, and on the other, it represents a detailed/invasive approach that was already becoming out of fashion, later editors (certainly after Rauch) confining themselves (in the main) to relatively sparing fingerings and bowings (as if to suggest possibilities rather than ‘prescribe’ an entire philosophy of performance, as might be said of David’s edition). The exception to this seems to be Ossip Schnirlin, particularly in respect of fingerings. As in other works he edited (such as the Brahms violin sonatas), Schnirlin’s editorial style included fingering alternatives – those in parentheses seem to be rather more stylistically-mannered than those that are not. Arguably, the content of these parenthetical markings links Schnirlin to 19th-century traditions and certainly, they suggest an older style of playing (with numerous encouragements of portamento, for example). Taken as a set, these editions act as ‘book ends’; in the middle, editions are relatively lightly marked with suggestions for practice (possibly aimed at the amateur market). Coming before this, David’s edition (as well, perhaps as that of Rauch) seems to suggest a personal understanding of Mozart’s music, as if editorial status conferred the responsibility of transmitting a performance tradition (an attitude surely cognate with Mendelssohn’s own ‘historical concerts’ at the Gewandhaus [see especially 93-96 in Milsom, 2008]. At the other end of this series, Schnirlin’s editions, with a heavy debt, it would seem, to the style and practice of Joseph Joachim at a time of rapid stylistic change, would seem to have a similar motivation – spelling out an established aesthetic as part the defence of a tradition under significant pressure from newer modes of expression as epitomised by the writings, editions and recorded performances of influential pedagogue, Carl Flesch (1873-1944).

Given the many correspondences between the violin and viola parts, coupled with the fact that only the violin parts are available in the Schnirlin edition, the foregoing more detailed remarks relate to the violin parts of these duos.

B3. a) G-Major Duo K. 423 –detailed remarks (violin part)

Dynamics

Of all of these editions, David makes the most changes in comparison to the Artaria edition, and thus creating a more varied landscape of dynamic values from what are, predominantly, generic f and p markings in the Artaria edition. At bar 11, only David specifies a crescendo, all of the other editions maintaining the f of Artaria. David’s detailed markings in bar 47 are also unique. Viewing the Schulz edition alongside David, it would seem that Schulz was aware of David’s edition, but, as elsewhere, it is the similarities between all editions after Schulz that is most striking (as seen by comparing bar 88, for example). Rauch’s edition seems to be based on Artaria (or possibly Hummel, as will be discussed below) and makes a number of independent expansions of such a scheme, although there are some eccentricities – it is curious that Rauch omits the piano at bar 21, for example. In the other movements, a similar pattern emerges. David adds a number of markings, Rauch rather fewer but with a clear awareness of first/early editions. At bar 5 of the second movement [Figure 12], Rauch places ‘sf’ at the start of the bar whereas David, Schulz and later editors indicate a crescendo – this implies a different understanding of the pacing of the phrase here and its ‘arrival point’:

Figure 12: Bar 5, movement II, K. 423 – David, Rauch, & Schulz editions

(David)

(David)

(Rauch)

(Rauch)

(Schulz)

(Schulz)

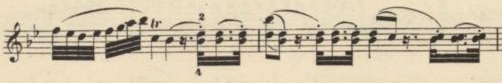

Bowing

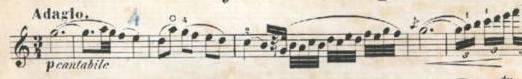

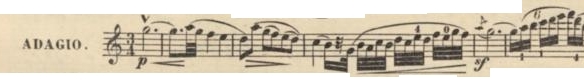

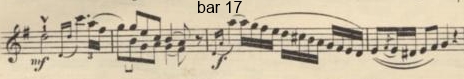

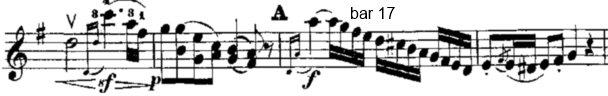

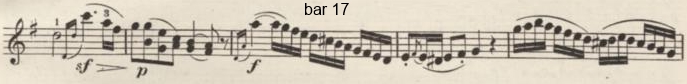

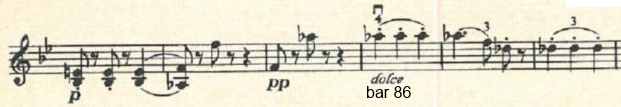

Rauch’s edition is initially similar to David’s at the beginning of the first movement, but very quickly he appears to exercise an independent editorial hand. As is evident in both Duos, Rauch can practice extremes as regards realisation of running 1/16-note figures, as can be seen at the beginning of this Duo [Figure 13]. At bar 17, the long slurring is distinct from David’s shorter groupings (and Schulz’s similar scheme), although at bar 19 Rauch, like David, creates shorter groupings and Schulz a longer, more legato line:

Figure 13: Bar 17, movement I, K. 423 – David, Rauch, & Schulz editions

(David)

(David)

(Rauch)

(Rauch)

(Schultz)

(Schultz)

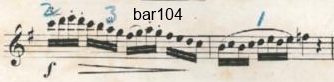

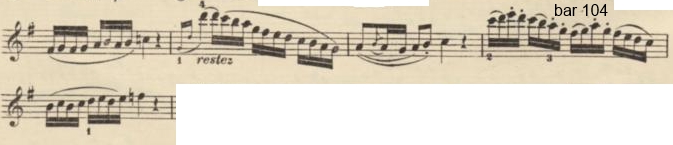

Generally, Rauch’s approach is to favour longer, more legato lines than David, reflecting perhaps a basis more in the cantabile tonal understanding of the post-Viotti period, whereas David (arguably) reflects an approach more cognate with our understanding of shorter, more articulate 18th-century ideals. At bar 104 of the first movement, however [Figure 14], Rauch’s approach seems more ‘mannered’ than David's in small-scale slurred groupings, making any form of chronological/editorial ‘narrative’ difficult to construct with confidence:

Figure 14: Bar 104, movement I, K. 423 – David & Rauch editions

(David)

(David)

(Rauch)

(Rauch)

The apparent basis of later editions in that of Schulz is suggested in respect of slurs and dots/strokes. This said, only Schulz changes the dots on the descending 1/16-notes in bar 1 to lines, but these lines seem to accord with David’s bowing scheme of seeing the dots (as so frequently the case in this tradition) not as off-string bowings (the spiccato or sautillé) but rather as on-string separations executed at the point of the bow – a matter made explicit in David’s edition by means of the down-bow sign on the trill note. Whilst others (including Schulz) execute the trill on an up-bow, Schulz’s lines seem to preclude this being an off-string stroke and suggests some similarity of technique. Interestingly, at bar 49, David uses lines and Schulz uses dots, which makes the issue as to exactly what distinction is to be made between these different signs somewhat uncertain.

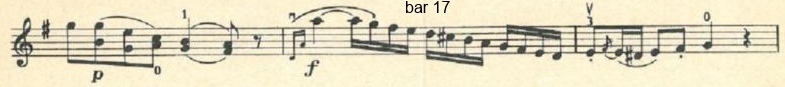

In general, as can be seen in the passage at bar 34, David has a tendency to reverse the normal direction of bowings, which tends to encourage use of the point of the bow and, importantly, means that David’s markings, if followed precisely, are clearly incompatible with 20th-century notions of bowing short/detached notes (often off-the-string, and more in the middle of the bow – which remains majority practice). In general, other editions can be bowed in this way or, equally, can be made to work ‘off the string’. Nor is David unique in such matters: in bar 17, for example [Figure 15], Laforge and Schnirlin imply an ‘upside down’ bowing of this passage:

Figure 15: Bar 17, movement I, K. 423 – Laforge & Schnirlin editions

(Laforge)

(Laforge)

(Schnirlin)

(Schnirlin)

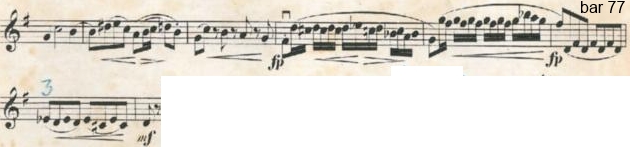

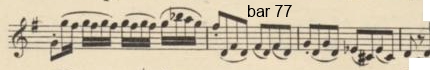

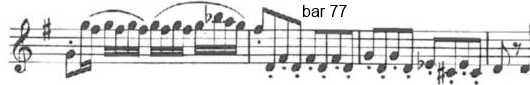

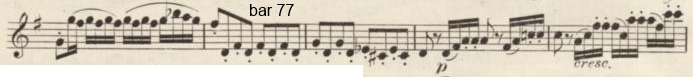

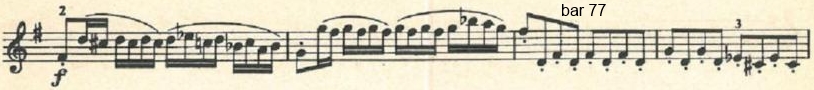

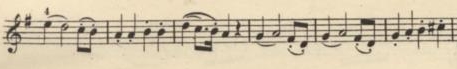

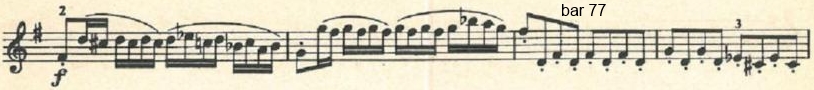

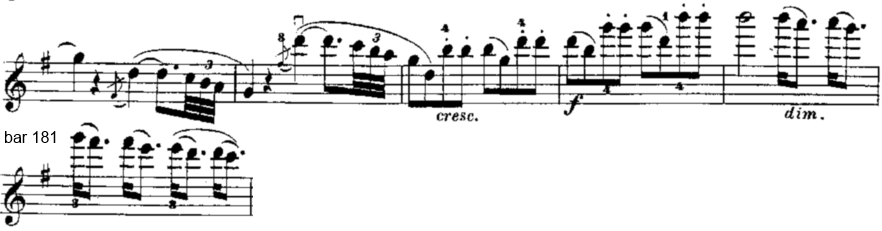

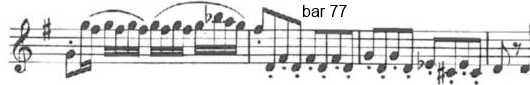

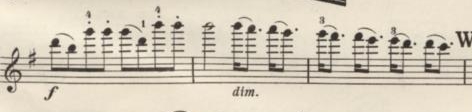

Indeed, a degree of individual variability of the editions can also be found, as at bar 77:

Example 16: Bar 77, movement 1, K. 423 – David, Rauch, Schulz, Hermann, Laforge, & Schnirlin editions

(David)

(David)

(Rauch)

(Rauch)

(Schultz)

(Schultz)

(Hermann)

(Hermann)

(Laforge)

(Laforge)

(Schnirlin)

(Schnirlin)

More fundamentally, however, it is notable that, taking David’s published and crayon markings together, his aesthetic was one of creating variation and intricacy to the performance by means of a detailed scheme as regards 1/16-note passagework – the other editors (with the possible exception of Rauch) take a simpler on- or in-beat approach to slurring. This can be seen by comparing David and Schulz in bars 100-101 [Figure 17]: here, the Artaria edition is also asymmetrically intricate (albeit in a different way from David) implying, perhaps, that such delicate variation of emphasis was expunged by the later editors but still evident in David’s scheme:

Figure 17: Bars 100-101, movement I, K. 423 – David & Schulz editions

(David)

(David)

(Schultz)

(Schultz)

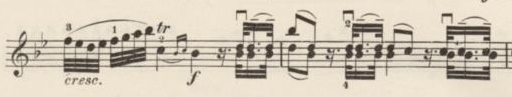

The second movement reflects a broadly similar approach across all editions, differences being relatively low-level and localised, although the slurred groupings in bar 6 and 12 show revealing similarities and differences maintaining the thus-far evident connection between editions. This is echoed in bar 12 – David and the Artaria edition phrase this in pairs, the other editions, including Rauch (and, possibly coincidentally, the 1783 autograph) have six 1/8-notes per bow.

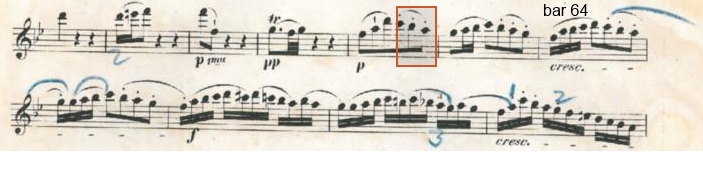

The Finale maintains similar traits. At the start, David is unique in changing the rhythm indicated in both the 1783 autograph and 1792 Artaria editions for 1/8-notes with corresponding rests, perhaps to ‘explain’ an on-string staccato mainly of articulation (separation) than accentuation. Hermann, Laforge and Rauch maintain Mozart’s separate 1/4-notes. David’s propensity for small-scale slur variability/complexity can be found in bars 16-17, whilst a degree of variation opens up in bar 64 [Figure 18]:

Figure 18: Bar 64, movement III, K. 423 – Rauch edition

The slurred staccato, a characteristic of the earlier part of the 19th century and Ferdinand David’s aesthetic (examples being found in, for example, the first movement of David’s 1866 edition of the Mozart Violin Sonata in B-flat Major K. 454, or in the Scherzo of Mendelssohn’s String Quartet no. 4 in E Minor, op. 44/2), can be seen here as well at bars 119 and 120 (David and Schulz), 174 (David) and, interestingly given the late date of the edition and as perhaps further confirmation of his ‘conservative’ artistic outlook, Schnirlin (bar 109, in parentheses).

The inter-relationship of the near-contemporaneous David, Rauch and Schulz editions can be seen by comparing the passage at bars 86-89 (Rauch reflecting the Artaria edition in bar 88) whilst at bars 101-102, Artaria, Rauch and Schulz show a clear if not exact parity, with David indicating shorter phrase/bow separations. Once again, however, David’s edition emerges from such a comparison as the most articulate, Rauch perhaps rather more ‘cantabile’ in approach overall, whilst Schulz and subsequent editors here creating something between these extremes.

Fingering

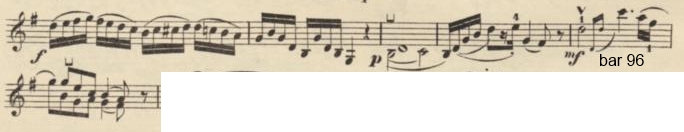

The Hermann and Laforge editions contain smallest number of printed fingerings of the editions examined here. It is interesting to note that some of the more ‘mannered’ approaches are to be found in Schulz (as at bars 39-40 in the viola part, as shown below) and indeed, Schnirlin. Rauch provides quite a large number of fingerings but these are mostly relatively straightforward and procedural although his tendency to favour a simple first- and third-position approach can result in the avoidance of open strings and 4th fingers (as at bar 59 of the first movement) with a readiness to allow for portamento to be included in the scheme, some instances of which can be conspicuous and even, arguably, a little clumsy, as at bar 96 [Figure 19]:

Figure 19: Bar 96, movement I, K. 423 – Rauch edition

In bars 21-22 [Figure 20], Schnirlin’s fingerings (including the option, below the stave in parenthesis, to remain on the A string and on the assumption that the notated 2nd finger in bar 22 is a misprint being in fact a 1/16-note early) imply a more complex and intricate scheme than the others:

Figure 20: Bars 21-22, movement I, K. 423 – Schnirlin edition

This is echoed later by an interesting passage at bars 118-124. David’s fingerings here, as in the rest of the movement, are relatively straightforward – favouring first and third positions, and integrating open strings and harmonics within the fingering scheme – and cognate with a tonal language that allowed for, and indeed encouraged, portamento. The fingerings do not, in all probability, place great emphasis upon the vibrato; this point can be made when comparing David’s edition with that of Joseph Joachim), as at bar 5 (David, Schulz and Schnirlin) or bar 38 (David). In the passage at 118 onwards, David does not print anything save for a simple shift from third to first position implied in bar 119. Schulz, however, preceding this passage with a sul D passage from bar 115 (as does Laforge) creates a more intricate scheme with implied position slides, whilst Hermann’s edition suggests a similar (if slightly simpler) solution. Schnirlin, in spite of some eccentricities in bar 112, follows the Schulz tradition.

In the second movement, all except Schnirlin start in first position and, with the exception of Rauch and Hermann (who do not provide a printed marking here) all of the other editions indicate a harmonic for the second 1/8-note of bar 3. Here, as elsewhere, it is Schnirlin who creates the most curious fingering solution, starting on a 3rd finger in fourth position (thus keeping the passage on the A string) – this may or may not indicate a vibrato on the first note, whereas the simpler solutions of the other editions suggest that such a consideration is less important, perhaps [Figure 21]:

Figure 21: Bars 1-4, movement II, K. 423 – Schnirlin edition

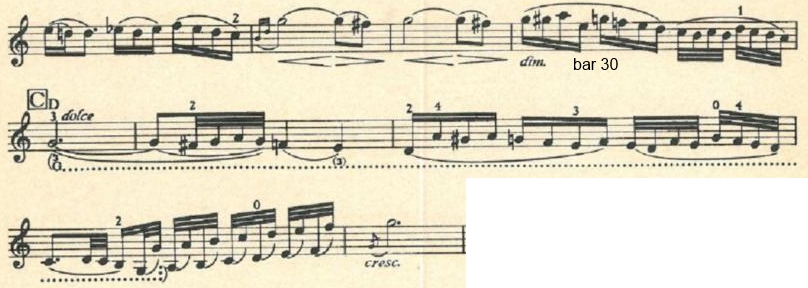

In bars 8-11, the relationship of later editions to Schulz’s edition can be found again (although Schulz’s fingering is very similar to David’s), whilst in bars 30-34 most (except David’s crayon markings and Schnirlin’s edition) imply staying in first position. David’s crayon markings as well as Schnirlin’s alternative scheme suggest a sul G realisation [Figure 22]:

Figure 22: Bars 30-34, movement II, K. 423 – David & Schnirlin editions

(David)

(David)

(Schnirlin)

(Schnirlin)

Rauch is alone in providing a fingering in bar 26 that implies a conspicuous portamento.

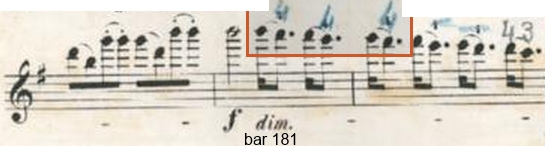

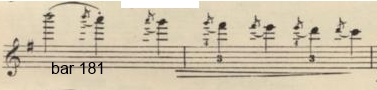

Similar traits characterise fingering schemes in the Finale (here, David, Rauch and Schulz are broadly very alike), albeit with some localised points of interest: in bar 32, Laforge’s fingering is unique, at bar 78 one notes David’s explicit employment of the open E string (creating a ‘bariolage’ effect), whilst at bar 181 [Figure 23] there is a particularly interesting example of David’s prevalence (found in many other editions, as can be found browsing the CHASE site) for consecutive ‘chains’ of portamenti on the same finger, as at bar 181, as opposed to slightly variant (but generally much simpler and less aurally conspicuous) solutions in the other editions:

Figure 23: Bar 181, movement III, K. 423 – David, Rauch, Schulz, Hermann, Laforge, & Schnirlin editions

(David)

(David)

(Rauch)

(Rauch)

(Schultz)

(Schultz)

(Hermann)

(Hermann)

(Laforge)

(Laforge)

(Schnirlin)

(Schnirlin)

As elsewhere, it is Schnirlin’s fingerings that appear to be the most curious. There are instances of fingerings with clear artistic motivation, such as the harmonics in bars 4 and 22, or progression up the same string with portamento implications in bars 76 and 107, whilst at bars 111-113 [Figure 24] the consecutive placement of the first finger is strongly suggestive of Joachim’s style and practice:

Figure 24: Bar 113, movement III, K. 423 – Schnirlin edition

In this context, David’s approach appears conservative, within the technical and stylistic context of nineteenth-century performing practices.

B3. b) B-flat Major Duo K. 424 – detailed remarks (violin part)

Dynamics

The opening movement provides a fitting focus for a discussion of dynamics in these editions. In the opening Adagio the 1792 Artaria edition has no printed markings, with the ‘f’ and ‘p’ markings in bar 1 at the start of each phrase being removed, compared to the 1783 autograph. Rauch adds little here, although his penchant for appending the word ‘espressivo’ at points in these Duos can be seen at the opening. It is possible that this has specific performing practice connotations such as, for example, the use of vibrato. David’s dynamics in 6 and 7 are echoed in Schulz’s realisation, but all of the later editions have the same markings as Schulz.

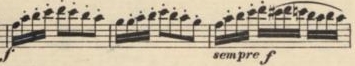

The same pattern emerges in the following Sonata-Allegro. Schulz maintains the Artaria scheme until bar 36, where ‘ff’ is added, although this marking (also found in Hermann) is omitted by Laforge and Schnirlin. Rauch marks dynamics lightly in this movement with some similarities to David’s added signs, such as the messa-di-voce ‘hairpins’ in bars 52-3. At bar 64, a difference does open up between Rauch and David (and Schulz) – Rauch’s ‘sempre f’ marking at bar 66 seems to re-enforce the continuation of a global forte in this passage as indicated by the Artaria edition, whilst Schulz and David imply a departure from it [Figure 25]:

Figure 25: Bars 64-66, movement I, K. 424 – David, Rauch, & Schulz editions

(David)

(David)

(Rauch)

(Rauch)

(Schultz)

(Schultz)

In comparison to Schulz, David creates a detailed scheme with a propensity for echo effects, as at the start. After the independence of Laforge and Schnirlin at bar 36, all continue to replicate Schulz – including the insertion of ‘pp’ at bar 85.

At bar 93, a more interesting difference emerges. Schulz and those after his edition use the ‘sfp’ sign found in the 1783 autograph (and the 1793 Hummel edition) but changed to ‘fzp’ in Artaria. Rauch uses a similar sign in variant form with ‘sf>p’ indicated. David, at this point, places ‘sf’ inside a messa-di-voce sign. This could be a simple difference of typesetting – the ‘sfp’ sign being by no means uncommon – or it may indicate that Rauch, Schulz and possibly the later editors had access to the 1783 autograph (or the 1793 Hummel edition, which uses this marking).

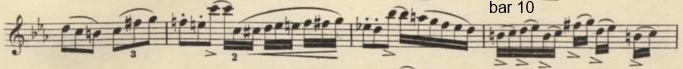

It is interesting to note that Mozart did not provide either Duo with many dynamic indications in their slow movements, possibly due to expectation of a freer approach to performance. In the absence of markings in early editions, it is notable that the later editors here provided their own schemes, none of which are especially out of the ordinary. An interesting difference between David and Rauch can be found at bar 10 [Figure 26]:

Figure 26: Bar 10, movement I, K. 424 – David, & Rauch editions

(David)

(David)

(Rauch)

(Rauch)

Rauch’s accent signs might imply a shading off of the slurred pairs here (in a manner obviously compatible with 18th-century practice) whilst David (and later editors, who follow a similar approach) stress larger-scale phrasing. Rauch is unique in the stepped ‘p – pp – ppp’ marking at the end of the movement, although it is highly probable that a similar effect was envisaged by the other editors, here.

In the finale, it is the earlier editors (David and Rauch) who provide the most detail, although Rauch provides little before Variation 3. A particularly interesting difference (pointing to the unique nature of Rauch’s edition in some respects) can be found at Variation 3, where Rauch reverses the understanding of the variation, seeing this as more robust ‘mf’ not an elegiac piano, whilst the situation is reversed in Variation 4, which Rauch marks ‘p’ not ‘f’. The difference of approach here is interesting, but it is equally curious that, in spite of a reversal of the dynamic schemes, all are united in the idea of a mood contrast between the two variations.

Bowing

Once again, all of the subsequent editions base their scheme on that of Schulz, or at least, Schulz, Hermann, Laforge and Schnirlin are very similar/identical, with David and Rauch emerging as comparatively independent editors. The opening Adagio is an exception, with a number of low-level differences between all editors, as can be seen when comparing the approaches to bars 6 and 7 [Figure 27]:

Figure 27: Bars 6-7, movement I, K. 424 – David, Rauch, Schulz, Hermann, Laforge, & Schnirlin editions

(David)

(David)

(Rauch)

(Rauch)

(Schultz)

(Schultz)

(Hermann)

(Hermann)

(Laforge)

(Laforge)

(Schnirlin)

(Schnirlin)

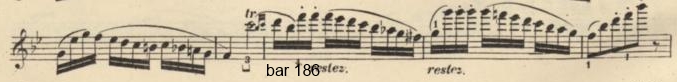

For example, at bar 36, David adds dots, whereas the other editors do not. At bars 52-3 editions after and including Schulz have separate bows with dots, whereas David joins these dotted notes under a slur. This slurred staccato is to be found in Artaria, but not in the 1783 edition. Bar 62 is also interesting in that David uses the slurred staccato, unlike the others. Rauch tends to formulate a more legato scheme in this movement, with longer slurs, as found when comparing bars 186-188 [Figure 28]:

Figure 28: Bars 186-188, movement I, K. 424 – Rauch edition

In the slow movement, Schulz indicates a simple bowing scheme, although in bars 24-5 Schulz’s slurring is longer than in Artaria (which is replicated in the other editions). At bar 10, Schulz employs a similar approach, although the other editors slurs these notes in pairs, as in Artaria. David’s bowing scheme is similar to the later editions, although at bar 7 (where Schulz and the others replicate the simplicity of Artaria) he indicates the more intricate scheme of cross-beat slurring found elsewhere.

At bar 15 [Figure 29], David and the 1792 edition indicate complex but differing bowing solutions, not replicated in the later editors (represented in the music example below by Hermann’s edition) who take a more straightforward approach:

Figure 29: Bar 15, movement 1, K. 424 – David & Hermann editions

(David)

(David)

(Hermann)

(Hermann)

One of the most curious markings is to be found in Rauch’s edition at bar 37, in which the separate strokes are explicitly indicated to be taken at the heel of the bow:

Figure 30: Bar 37, movement II, K. 424 – Rauch edition

In the Finale, similar broad themes emerge, although (as at the opening of the Finale of K. 423) one notes that David changes Mozart’s 1/4-note rhythm at the opening for 1/8-notes and corresponding 1/8-note rests, taking these as separate bows. Schnirlin also has this figure separate bows, as in Artaria, without resorting to David’s manipulation of Mozart’s rhythm, whilst Schulz and Hermann slur the 1/4-notes in pairs, with Laforge, atypically, emerging as independent with slurs across the second and third 1/4-notes. Rauch’s scheme integrates a degree of detailed small-scale slurring and phrasing (as in the overtly ‘virtuoso’ material in Variation III), whilst at the same time also including some unusually long slurs, as at bar 75 and 79, the latter of which sits oddly with the simultaneous forte dynamic marking.

Fingering

In this Duo, David perpetuates what appears to have been a general tendency to remain in positions and shift (with possible portamento implications) on the same strings to maintain continuity of tone colour. In addition, the legato conception of cantabile passages is conveyed by shifts between smaller intervals – this is well demonstrated by his fingering at bar 6 of the opening Adagio with his shifts up the A string. Consecutive uses of the same finger (including 4th fingers), found in many of David’s editions (as printed and, in the Uppingham collection and the Bodleian Library/Alan Tyson material, in hand-written markings) are also indicated, as at bar 56.

As elsewhere, Schulz, Hermann and Laforge are clearly related in terms of fingering patterns in this movement, with Schulz giving rather more in the way of printed markings than the others. Rauch appears, as elsewhere, largely independent, albeit with some (perhaps inevitable) similarity with other editions. Schnirlin, on the other hand, maintains his tendency to mark the edition more heavily – his fingerings are often independent of David’s but reflect if not his stylistic approach then certainly one that implies an aesthetic rooted in the nineteenth century. At the opening, only Schnirlin indicates anything other than first position. At the D♭-Major statement of the theme at bar 86 [Figure 31], he indicates an expressive fingering with implications mainly as regards portamento:

Figure 31: Bar 86, movement I, K. 424 – Schnirlin edition

In the slow movement (and Finale), save for an individual and slightly eccentric approach by Laforge to bar 32, or Rauch’s unique instruction to remain on the A string in bar 26 (both in the slow movement), the same pattern emerges.

Looked at overall, David’s edition in the context of these later examples shows him to be a quite comprehensive editor – his printed markings give a more complete understanding of an expressive performance than the others, with the exception of Rauch and Schnirlin. The other editors (with the possible exception of Schnirlin) appear to be more indicative than prescriptive, and it seems plausible, given the many similarities between them that there is some awareness of each other’s editions. Hermann, certainly, seems to be aware of Schulz’s work; whether the similarities between the editions suggest that Laforge and Schnirlin are aware of Hermann or Schulz is a little difficult to ascertain with certainty, but they do appear to reflect a knowledge of at least one of these earlier editions. Rauch’s edition appears both cognate with those of David and Schulz respectively whilst, at the same time, exercising obvious independence, and including a number of eccentricities in all three parameters examined in this brief study. Schnirlin’s alternative markings (in parentheses) seem to suggest an ‘artistic’ mode of performance, and there are notable similarities between his style of fingering here and the Joachim ‘aesthetic’ – a little more complex than David (with fewer instances of consecutive uses of the same finger, for example). Whilst the potential for the portamento is quite obviously implied by fingering schemes (although essential aspects of speed, type and volume are, of course, not indicated by finger numbers alone), less frequently reported is the issue of the vibrato implications of a fingering. Although the vibrato (in the modern intonation definition of the term) is practicable on all four fingers, one should note that a fingering scheme integrating stopped notes with open strings and harmonics, as well as prominent uses of the least-conducive finger for the vibrato (the fourth finger) is unlikely to consider the vibrato to be a frequent and dominant feature of the sound. (The obverse of this situation is that 20th- and 21st-century fingerings can contrive to use fingers 1-3 in order to favour the device.) Schnirlin is clearly motivated to create a colourful artistic realisation which, given the number of harmonics and open strings as part of the fingering scheme as well as fingerings suggestive of expressive shifting, implies that his artistic model is not so much the newer modes of expressivity of his times (favouring vibrato via the avoidance of open strings and 4th fingers) but rather established 19th-century ideals.

________________________________________________________________

TITLE PAGE, Abstract, Acknowledgements, Citation

Part A: INTRODUCTION (David Milsom & Clive Brown)

Part B: FERDINAND DAVID’S EDITION IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT (David Milsom)

Part C: PERFORMING FERDINAND DAVID’S REALISATION OF THE MOZART VIOLIN & VIOLA DUOS (David Milsom & Clive Brown)

Part D: EXPERIMENTAL RECORDINGS (Clive Brown – violin; David Milsom – viola)

Part E: CONCLUSIONS (David Milsom)

Part F: LIST OF REFERENCES